“Why are Holocaust survivors obsessed with future generations remembering? Why do they command us all to Zachor, to remember? What is it they want us to remember?” That is the challenge every post-Holocaust generation will continue to face, just as all Jews at the Passover Seder are asked to think of themselves as slaves freed from Ancient Egypt. The significance of re-thinking the past and what it means in the present is best explained by Leon Wieseltier, social critic, literary editor of the New Republic and a 2G—second generation descendant of a survivor—who writes, “A tradition that is transmitted more or less as it is received will not live long.” Survivors wonder if the 3Gs—third generation descendants—will continue to tell of the destruction of European Jewry, or if the story will die with them. It took two generations—40 years—for the silence to be broken, for psychological denial to erode, and for survivors to have an audience that did not silence them the moment they attempted to share the stories of their horrific experiences. Parenthetically, it took 40 years after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain before the liturgical poems to commemorate the loss of that era were written. And after slavery in Egypt, according to tradition, God waited 40 years before deciding that the Israelites were ready to the enter the Promised Land.

Sixty-three years after the liberation, is there an identifiable group of Third Generation descendants of Holocaust survivors? Second Generation became a visible group in America in the mid-1970s, when a large cadre of survivors’ sons and daughters in their 20s searched for their own identities—along with others in the “roots” generation.

The Second Generation was transformed from invisible to visible with the publication of Helen Epstein’s watershed New York Times Magazine article, “Heirs of the Holocaust,” on June 19, 1977. It was read by more than 2,000,000 people nationwide. The article described awareness groups for children of Holocaust survivors that Bella Savran and I led in Boston, inspiring others to begin similar groups elsewhere. Grassroots activities were reinforced by the publication of Epstein’s book Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors, followed several months later by the First Conference on Children of Holocaust Survivors in November of that year.

The conference brought approximately 600 participants to New York City from all over the United States. In June 1981, many of these same young adults accompanied their survivor parents to the World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors in Jerusalem and formed the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors. The political, educational, and commemorative activities of this international organization, along with local groups, gave the Second Generation a voice of moral authority.

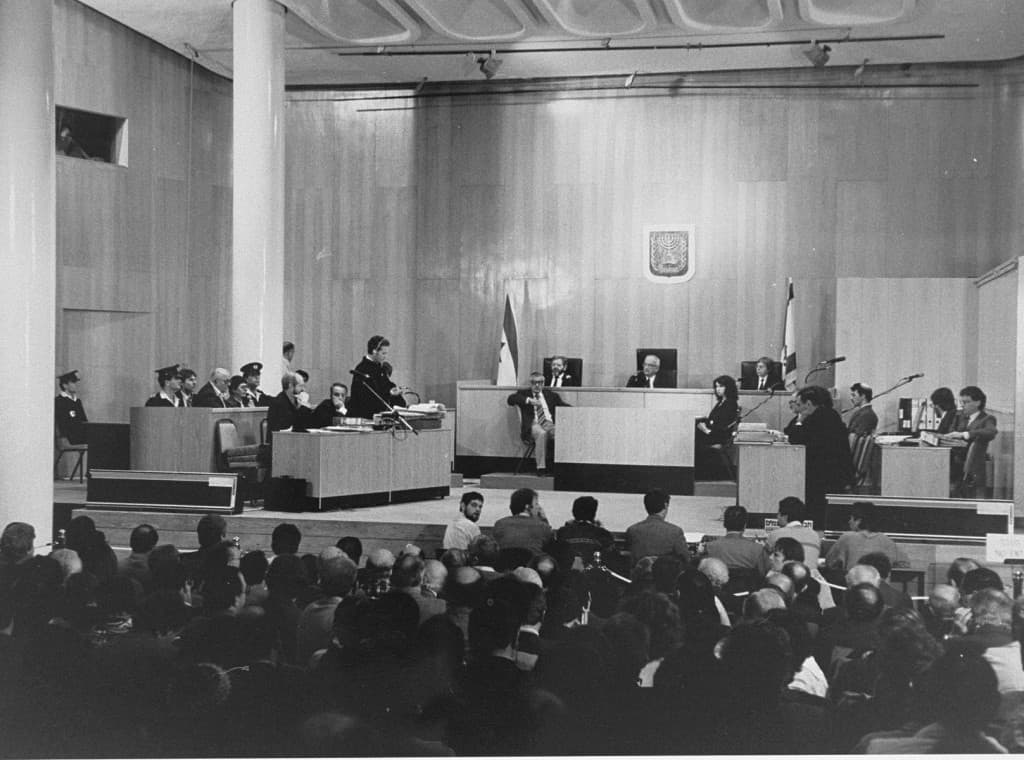

The Third Generation coalesced as a group in Israel—not in the United States. During the Demjanuk war crimes trial in 1985, Israeli teenagers flocked to the court house, lining up at dawn to try to get seats inside.

At the same time, Claude Lanzmann’s marathon movie, Shoah, was screened. Many youngsters saw survivors being interviewed on-screen about their lives in concentration camps, in ghettos and in hiding. In hearing of their escapes and of masquerading as non-Jews, the Third Generation was learning its grandparents’ history, imbibing the language they would need in order to communicate with them.

Many of these high-school students found their own parents to be virtually useless when it came to answering questions about family history. And yet, without hesitation, they approached their grandparents and simply asked them for their stories. This phenomenal intergenerational dialogue became a national sensation recorded in documentary films and television programs.

Nava Semel’s novel, The Rat Laughs, begins with a granddaughter wanting to know what happened to her grandmother, the Holocaust survivor, and what would happen to her memories in 100 years. The Rat Laughs was adapted as an opera and regularly performed at the Cameri Theater in Tel-Aviv.

Psychologist Dan Bar-On, and his students (like Julia Chaitin at Beer-Sheva University) researched this phenomenon in Fear and Hope and Children in the Shadow of the Holocaust (Julia Chaitin and Zahava Solomon, in Hebrew). They found that survivors found it much easier to communicate with their grandchildren than with their own children. The 3Gs normalized the process of dialogue. Bar-On and his team developed a paradigm for working through the Holocaust through knowledge, understanding, emotions, attitude, and behavior. They discovered that for 3Gs, the Holocaust either has no relevance—“under generalization”—or it has so much relevance, everything is seen through its prism—“over generalization.” A normal reaction to a Shoah family background is “partial relevance”: A moderate and more balanced perspective.

When Julia Chaitin interviewed survivors—2Gs and 3Gs in 20 Israeli families—she discovered a fourth reaction, one of “paradoxical relevance.” She posits that “under generalization” does not work in Israel because the Shoah keeps popping up, and some 3Gs cannot understand it at all. Others react with emotion but have no detailed knowledge of their grandparents’ survival. On the other hand, they may have an abundance of information and no emotion. These individuals know where their grandparents came from, what they suffered, but personally feel distant from the events. Then there are those who are haunted by their grandparents’ Shoah past, but do not know the significance of their family history.

Compared to the 2Gs, the 3Gs have a more balanced view. They did not grow up with the concept of “Jews who went like sheep to the slaughter.” The 2Gs heard this many times from the non-survivors around them. Many had parents who were ostracized and shunned as victims. The 3Gs also lack deep-seated fears of antisemitism, fears that are generally more pervasive in the lives of Holocaust survivors and 2Gs.

The 3Gs in America only recently became visible group, but with less intensity than the 2Gs. Demographically they range in age from newborns to 40-year-olds. 3Gs in their 20s and 30s are grappling with identity formation, with establishing intimate relations, and with having children. The 3Gs have no collective voice that distinguishes them from others in their generation, with the exception of those who participate in the March of the Living pilgrimages to Poland, where they light memorial candles, share their family narrative, or say Kaddish for those who were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators.

In the United States, intergenerational communication is similar to what is found in Israel—specifically that it was easier for survivors to share their stories with their grandchildren. Psychologist Bonnie Bienstock also found that survivors have a warmer relationship with their grandchildren than do American Jewish grandparents.

The flood of psychological research on the impact of the Holocaust on 3Gs follows a parallel pattern, similar to research on the 2Gs. Articles in psychological journals on the subject started with a case study of an emotionally-disabled grandchild of survivors in treatment, and concluded with generalization to the group as a whole.

A note of caution is necessary to readers of professional and popular publications: The reader must be aware of the sample being presented. In most cases it is challenging to get a representative sample of this population in order to generalize findings. Also, most studies are based on very limited or skewed samples (e.g. hospitalized grandchildren of survivors or those in psychological treatment).

There is also a phrase that repeatedly crops up when 2Gs and 3Gs are discussed: “intergenerational transmission of trauma.” It is a phrase with negative connotations, and an a priori assumption that all effects are emotionally debilitating. The phrase has been misused since 9-11. According to Freud, trauma is an overwhelming experience that emotionally shatters the person who is going through it so that s/he cannot cope. Trauma cannot be transmitted to others. 3Gs are not experiencing Nazi racism or genocide. What is transmitted to 3Gs are values, worldview, family interaction and love—not trauma. It is time for this hackneyed phrase to be retired. 3Gs are not suffering from “silent scars.”

Being a 3G is not a personality syndrome. Grandchildren of survivors do not exhibit more depression, more anxiety, more psychosis, borderline-narcissistic symptoms, or any other diagnosis than do comparable groups. A Montreal survey by John Sigal and Morton Weinfeld found that 3Gs function better than similar groups whose grandparents came to Montreal before World War II. 3Gs tend to be more affectionate, happy, friendly, self-confident, peaceful, and easy going.

From the psychological research the only significant finding is that grandchildren of survivors as a group are higher achievers than their peers. In 2002 Ellisa Ganz found that 3Gs, like 2Gs, are twice as likely to choose an occupation in the helping professions. Ganz also found, however, that those 3Gs who are in therapy are in treatment for longer periods than comparative groups.

Flora Hogman conducted a case study of 2Gs and 3Gs, and noticed that in her sample of the grandchildren, there is sense of pride in—and awe of—the survivors. This awareness of the suffering that grandparents endured is part of the fabric of their lives, but it is channeled into empathy, political activism, greater consciousness of others’ suffering, and a reluctance to intermarry.

The above findings are further elaborated in Mark Yoslow’s recent doctoral dissertation The Pride and Price of Remembrance: An Empirical View of Transgenerational Post-Holocaust Trauma and Associated Transpersonal Elements in the Third Generation. He acknowledges “the Third Generation takes great pride in being the scion for the family that survived the Holocaust.” Feelings of anger and PTSD symptoms decrease if one is not driven by apocalypse and by an archetype of Nazi Germany.

He goes on to explain a presence of a “culture complex,” which shows that when individuals can experience “dispositional forgiveness”—the ability to forgive trauma within oneself rather than forgive the Germans—they are able to escape post-Holocaust trauma. Yoslow observed that the 3Gs have a deep affection for humanity, which is a transformation of the post-Holocaust trauma. This process is the ability to transform the emotional effects of the Holocaust by letting go, and thus increases the quest for meaning in ones life and concern for social issues.

I interviewed grandchildren of survivors for whom the Holocaust is a central part of their identities and found that they had a close intimate relationship with one or more grandparents. This relationship increases the propensity to embrace a commitment to remember the destruction of European Jewry. A second factor that enhances the propensity towards Holocaust remembrance is a strong Jewish education that combined the Shoah with other relevant historical understanding of Jewish peoplehood.

Today, 3Gs whose professional lives have been shaped by their grandparent’s ordeals are found in the creative arts, in helping professions, human rights work, and in Jewish studies and communal work. The 3Gs are no different from those 2Gs who gravitated towards the creative arts in order to remember the barbarity committed against the Jews living in German-occupied countries and the Jewish life that was destroyed.

3Gs like Dan Sieradski, now in his late 20s, have created Jewish communities both online and off, in Israel and the U.S., that are life-confirming and committed to exploring Jewish tradition. Aaron Biterman created a Facebook for 3Gs that now numbers more than 500 participants. They raise consciousness about present-day racism, human-rights violations, and genocides. Everyday one hears of new projects—a musical to commemorate the courageous deeds of Raoul Wallenberg and a film on the American eugenics movement and how it influenced Hitler’s Final Solution.

Much attention was paid to Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2002 novel, Everything is Illuminated, in which a 3G goes out to find the woman who may or may not have saved his grandfather from the Nazis. He tells a tragic story with wit, truth, and humanity. Poet Sabrina Mark’s imagination published in her book Babies is eerie. “…..It is lonely in a place that can burn so fast.”

This is a trans-national phenomenon. In Israel, for example, Miri Ben Ari is a Hip-Hop violinist who won the Grammy and the Israeli Martin Luther King Jr. Award for her song and video “Symphony of Brotherhood,” a unique attempt to reach African-American youth through culture.

Some 3Gs are gravitating towards interacting with others from similar backgrounds. Daniel Brooks attended a 2G meeting and felt that he did not belong, and so he founded the “3GNY” group. Today, hundreds of young adults are meeting on a monthly basis to share a common family history, to socialize, and to educate themselves about common political concerns, such as Israel, Rwanda, and Darfur.

Daniel Gillman, a sophomore at Brandeis University, is always on the lookout for Holocaust-related programs. In the spring of 2008, Gillman drove all night to meet diplomatic rescuers at Ellis Island’s Visas for Life opening program for the exhibit. He is Charlotte Gillman’s grandson, and she is one of three hundred children saved by Père Benedictine monks in Bruges, Belgium. When he was 12, Charlotte took him to Belgium, and he has since eagerly listened to her stories and to his aunt, Flora Singer, who wrote I Was But a Child. This summer he will be an intern at the Office of Special Investigations at the Justice Department and will assist with Nazi War Crimes cases.

There has been a paradigm shift between 2Gs and 3Gs. As the world has validated the suffering and resilience of the Holocaust survivors, the central dynamic has shifted from shame to pride. With 3Gs like Jody Rosensaft, Jessica Meed, Elana Berkowitz, Daniel Brooks, Daniel Gillman, Danielle Tamir, Neil Katz, Dan Sieradski, and Leora Klein, the Holocaust survivors can rest assured that the Third Generation will not forget their great grandparents—or their experiences. The Holocaust will never be forgotten.