I am an adult child of Holocaust survivors born in a half bombed out hospital in Kassel, Germany. For me, the whole notion of the Holocaust evokes never ending questions about human beings who annihilate other human beings for who they are. Death in war is one thing, but how do you justify systematically dehumanizing a group of people on an ongoing basis and then slaughter them? How do you blame starving babies and children for the ills of society and starve them to death?

When I was a child, I never gave these questions a second thought. My father and mother were not wont to describe the gory details of their ordeals. I heard bits and pieces as they sat with other survivors. As a teen ager and young adult, when I went shopping with my mother on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, she would ask every store owner with an accent “Where are you from?”

Stories, places, names, would be exchanged, and I heard about the panorama of Jewish life and survival before, during and after the “war.” Satmar Hassidim and people who openly denied their Jewishness all responded to my mother’s questions. I realized that survivors had shorthand conversations, and after a while, I picked up the “code.”

I never realized that these shopping outings would get me more than outfits. Today I am obsessed with my people’s history and the questions it raises. My shopping experiences prepared me to ask fellow children of Holocaust survivors about their family histories.

In 1976, when I started the first groups for children of Holocaust survivors with Bella Savran, also a child of survivors, I could help others ask their parents questions they themselves never dared raise themselves. I would ask potential group members to tell me about their parents’ lives before the war, and a new awareness would be set in motion. Children of survivors would begin to realize that their parents were not just Holocaust victims or heroes; they were people. My interviews helped them integrate their perceptions of their parents in their own minds.

And when members of the second generation would meet with others of similar background, they automatically bonded and understood each other, creating a family like feeling.

It was interesting to see how different offspring of survivors integrated their parents’ experiences into their lives. On the one hand were the second generation individuals who were completely dysfunctional and blamed everything wrong in their lives on their parents and the Holocaust. On the other were those offspring for whom the Holocaust was an impetus to make the world a better place and understood that they were responsible for their own actions.

I discovered that among many second generation members, there was a sense of moral authority that came from confronting the injustice of the Holocaust and the silence of the peoples of the world. I became curious about those second generation people who felt compelled to grapple with moral questions.

What I discovered is that despite the heterogeneity of the offspring of survivors, their actions stem from a moral conviction of responsibility to the dead, the process of mourning is the impetus for action.

Speaking up for moral causes is a constructive way to channel feelings of mourning that are aroused in the members of the second generation. Although members of the second generation did not experience direct losses, they still do mourn relatives who were murdered and for whom most of them are named. The mourning is also for the destroyed communities, roots, possessions, family heirlooms, and with it, a destroyed vibrant Jewish tradition and culture. For some children of survivors, the unfulfilled hopes and dreams of their parents and the dead are an inspiration to prevail and thrive. For others, it becomes a burden. It is beyond the scope of this writing to analyze those who have been impaired during the mourning process. Suffice it to say that there are many factors that are attributed to the inability to mourn.

For the moral voices of our generation, their inner core withstood the transformation one undergoes once he or she faces multiple losses. The mourning process begins with a sense of shock. Many children of survivors stumbling across photographs of piles of bodies, or hearing they had a sibling who was killed, or seeing the number on their parents’ arms. Getting the right answer, rather than “that’s a telephone number I can’t remember” when they ask “Mommy, what’s that number?” puts them in a state of disbelief. This early phase is usually followed by denial. This is psychological denial, as opposed to historical revisionist denial. The third phase is confrontation. This process entails finding out details of what happened. With confrontation follows the feeling stage of mourning anger, rage, helplessness, sadness, depression, isolation, anomie, undoing, and guilt.

At this stage, a transformation needs to occur if one is to get to a state of action. Responses at this phase take various forms: creative endeavors, consciousness raising, research, social action, education, community building, helping others, and commitment to restoring and continuing Jewish life that was destroyed.

Just as the phases are not linear, so too, the responses are not unidimensional. The moral voices of our generation are absorbed in a myriad of endeavors from being Jewish community leaders to dealing with domestic violence issues on a one to one basis. Such behavior becomes the core of one’s being and manifests itself as situations warrant.

For me, the moral questions raised by the annihilation of an entire group of people became the focus of my graduate work in social and personality psychology at the Graduate Center of City University of New York (CUNY). There I met others who were grappling with similar questions. How does one maintain moral integrity under extreme circumstances when the authority is malevolent?

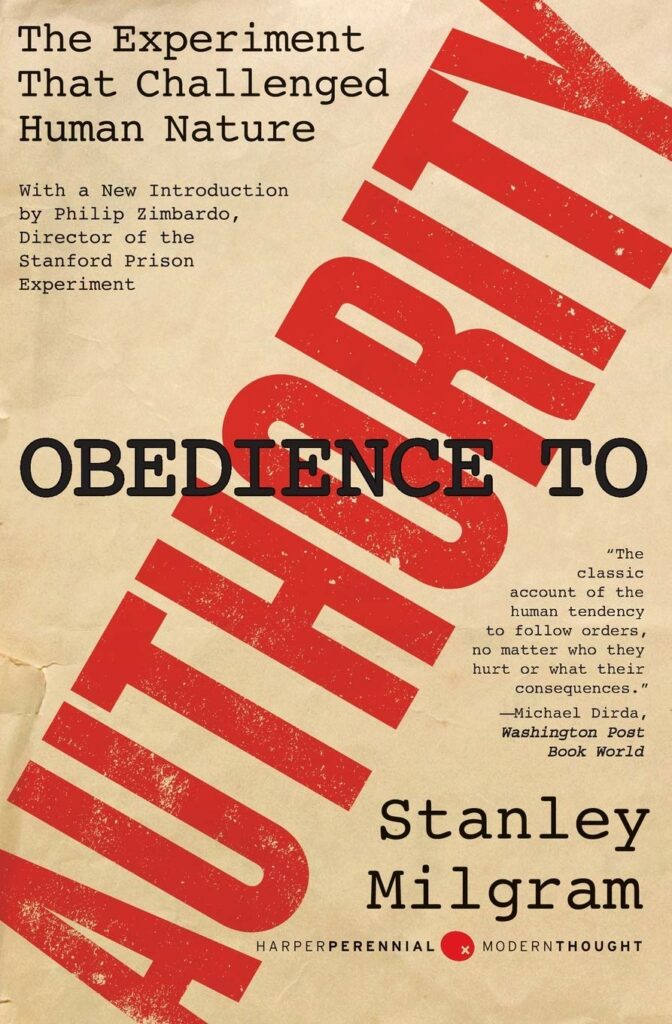

One of them was Stanley Milgram, whose ground breaking book Obedience to Authority, found that most people surrender personal responsibility if their actions are dictated by authority figures. Milgram’s proof was based on his own laboratory experiments where people were ordered by others in authority to give electrical shocks to others who could not remember word associations. In reality this was a simulation and the shock machine was inoperative. In years to follow he was blamed for carrying out unethical research. In my view, this accusation is itself a form of denial and avoids confrontation with “real” persecutors.

Being interested in moral capacity in human beings, I was intrigued by the minority in Milgram’s study who disobeyed authority. What enabled them to maintain their moral integrity?

My specific pursuit stems from my parents’ accounts during the German occupation years. When the Germans rolled their tanks into Illya, a Byelorussian town 100 miles east of Vilna, they issued an endless stream of restrictions, directives, and orders aimed at Jews. On Purim, March 20, 1942, the Germans intercepted Jews on their way to work and marched them all off to the village square. One thousand Illyan Jews, among them my father’s aunt, uncle, cousins and friends had been slaughtered. They missed my father because he was already at work in the village bakery.

When the Gestapo burst into the bakery to search for Jews who had slipped through the roundup, the Russian supervisor confidently told them, “No Jews here.” By the time they returned the following morning, the supervisor had helped my father escape into the woods and meet up with the few Jews who survived the massacre.

While my father hid in the woods, a poor farmer helped him. During the night, the farmer would send his children to my father with food and with ointment for his lice infested hair. They would also take his clothes to be washed. When winter approached, the farmer, Ivan Safanov, arranged to have my father join the Byelorussian partisans. He survived the war and fought the enemy.

My understanding of morality under conditions of extreme terror became more complex when I learned that another colleague at CUNY, psycho historian Robert Jay Lifton, did not discover any trace of guilt in the Nazi doctors he interviewed from the late 1970’s until the early 1980’s. The doctors were not just following orders or doing their duty. Lifton found that they strongly believed they were contributing to a biomedical ideology devoted to eliminating the “germ carrier” that prevented the development of the Aryan race.

I realized that those who risked life and limb to save Jews needed courage to act on matters of conscience. Previously I had thought that those who did save Jews had to be saints.

In the early 1980’s, when I began to voice interest in these moral issues, I discovered that most people were suspicious of altruistic behavior. People would say, “The rescuers must have had ulterior motives.” Holocaust survivors would say, “Don’t make such a big deal about the rescuers; there were so few.” Psychoanalysts say that altruism does not exist; unconscious motivation, narcissistic gratification, are at the core of helping others.

They didn’t convince me. It seemed to me that it took extraordinary courage to act to save a Jew when it meant death. I felt that if we could understand the rescuers, we could understand the idle bystanders and the Nazi collaborators.

In 1981, I traveled throughout the US, Israel, and Europe in search of rescuers. The details of my findings were recorded in my doctoral dissertation, and in my 1994 book, Conscience and Courage: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust.

When I present the results of my research to audiences, people inevitably ask, “What would I have done under similar circumstances?” We do not need life and death situations in order to speak up for tolerance and for the acceptance of people who are different. I ask my audiences to think about what each person does today, rather than ponder hypothetical questions like, “What would you have done 50 years ago?”

I also wanted to know whether other children of survivors were also plagued with moral questions and action. And if they were, what form did this morality take in their everyday life? I did not have to look very far.

Menachem Rosensaft, a New York attorney, was the founding chairman of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, Inc. He was among those who brought children of survivors together at the Kotel (Western Wall in Jerusalem) in 1981, to join the Holocaust survivors at the World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors. There, the second generation took a pledge to carry on commemoration, education, and Jewish continuity. Rosensaft and the others, myself among them, acted out of a sense of moral responsibility to the dead.

Through the network he and his colleagues created, children of survivors, as a group, became a moral voice in the American Jewish community and in the international political arena. “One of my goals,” Rosensaft told me, “was to make sure that the second generation not be introverted, but instead also look out to human and social issues affecting the community as a whole, which is why we were the first group to organize a New York City wide rally on behalf of Ethiopian Jewry 1982.” He adds, “we also were a lead factor in the opposition to President Reagan’s decision to visit the German military cemetery at Bitburg in 1985, probably the one organized group to be consistently and vocally opposed to the President laying a wreath at the graves of the Waffen SS. On May 5, 1985 Rosensaft led a demonstration of second generation members at Bergen Belsen against what he called Reagen’s “obscene package deal” of Bitburg and Bergen Belsen mass graves.

Other children of survivors used their moral voices at different institutions, Jewish and secular. From the World Jewish Congress to the halls of the United States Congress, there are children of survivors who work on making the world a better place, while others prefer to express their moral convictions through their writing, research and artistic enterprises.

One prominent writer is a social and literary critic, Leon Wieseltier of The New Republic. Wieseltier’s mother, Stella, a Polish survivor, worked at the very first Holocaust resource center established in the United States, the Brooklyn Center for Holocaust Studies founded by Dr. Yaffa Eliach, in Brooklyn in the mid 70s. Wieseltier does not miss an opportunity to speak up for the dead and restore their dignity when they are desecrated. When the memory of murdered Jews was being profaned at Auschwitz by Carmelite nuns who wanted to obliterate their memory, Wieseltier revived the honor of those Jews on the op ed pages of the New York Times. His eloquence, his piercing words, his candor caught the attention of the body politic: “It appears that Auschwitz has lost none of its power to derange. Nobody dies there anymore; but decency still does.”

In my role as a social psychologist, I conducted in depth interviews with some of these moral voices and leaders in the community. I wanted to find out if and how their parents’ experiences under the Third Reich inspired the work they do. I did not directly ask questions about moral conviction. I derived my conclusions from a sequential analysis of their feelings and thoughts expressed during the interviews, and from their writings, and speeches.

I chose these people because I feel they have clear moral voices. I feel that they act on the courage of their convictions, even when others criticize them. These people, all prominent in the American Jewish community, have, at least had an impact on their local communities. Some have national and international reputations, and their voices make a difference in the lives of oppressed people, against injustice, bigotry, intolerance, and racism in the present and the past.

In some cases, people risked their lives to help others in distress. Whether they did so consciously or not, each person is carrying out a mission that was imbedded in his or her being. I found that the “moral self” was represented in a variety of political and social arenas, from prosecuting Nazi war criminals to rescuing Jews from the former Soviet Union to raising objections to the rise of subtle and not so subtle antisemitism in the world and in Germany today.

One person refused to be interviewed for the study. Although his voice openly reflects a moral responsibility to the dead, he felt that if I grouped him with others who had similar convictions, it would somehow diminish his unique voice. When one is pegged with an identifiable group, all the stereotypes, positive, but most often negative, are attributed to him or her. By remaining separate, a person may think that he avoids being typecast, and holds onto his uniqueness, when in reality such thinking is erroneous.

Another interviewee wanted to remain anonymous because she felt that her work which involves bringing Nazi war criminals to trial would be labeled as revenge if people knew that she was second generation. She has already had this convoluted defense used against her in court, as have other lawyers with similar backgrounds. I respect her anonymity and have disguised her identity.

Some interviewees are very open about their family history; others are more private. I was not surprised to find that even among those who were generally knowledgeable about their parents, some did not know the details of their parents’ ordeal. The interview process, in some cases, sent them back to their parents to ask more questions. Others live and breathe the murder of each relative.

How does this second generation voice manifest itself? Let’s examine the Middle East peace process. There was an inability to sit down with Arabs who killed Jews in a war of attrition that benefited neither side. The world was looking for a survivor who could give a green light to open negotiations with Yasser Arafat. If those who were the most vulnerable would have the courage to sit and talk with the enemy, then perhaps others would be swayed to move towards peace.

While the survivor community on the whole opposed such a step, Menachem Rosensaft took the risk and traveled with four others to Sweden to meet with Arafat. He was initially shunned by the Holocaust survivor community and members of the organization he helped found, as well as by virtually every American Jewish organization. It was clear the community was not ready to face the consequences of a failed effort towards peace.

Rosensaft’s parents, the only remnants of their respective families, have been role models who prepared Menachem to be a spokesperson for the second generation. His father, Josef (Yosele) was leader of the Bergen Belsen Survivor’s Association in particular, and a leader of the non Orthodox she’erit ha’pletah in general. This kind of landsmanshaft was a self help group for the remnants of European Jewry who had no extended family with whom to celebrate life cycle events and holidays.

Yosele and his wife Hadassah were the last ones to leave the Displaced Persons camp in Bergen Belsen, where for five-and-a-half years he assisted and guided survivors to make the transition from being victims to liberated people. Menachem was born there in May, 1948.

Yosele worked with Nahum Goldmann, president of the World Jewish Congress, to force the German government to provide restitution to its victims. (In 1953 the German government agreed to pay Holocaust survivors reparations for any physical or mental damage they suffered under their occupation.) The “landsmanschaft” Yosele helped establish commemorated the liberation of Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945 long before Holocaust commemorations ever came into vogue.

Conversations about the war in Rosensaft’s house did not focus on gruesome details. His mother, Dr. Hadassah Rosensaft, was a heroine. During her incarceration in Auschwitz, she lost her five year old son but went on to save hundreds of women in the infirmary. She risked her life for some 150 children at Bergen-Belsen by bringing them extra milk, food rations, and scarce medication after she was transferred there. When the war was over, she accompanied these orphans to safety in Palestine, and then returned to war torn Europe to help other survivors.

In 1950 the Rosensafts moved to Switzerland to recuperate before they found a permanent home in New York. They would have preferred to live in Israel but ultimately did not do so for personal reasons. Yosele, who was involved with the Israeli leadership through David Ben-Gurion and others, stayed in close touch with Israeli officials who frequented their home, and Menachem celebrated his bar mitzvah in Israel, celebrating with other members of the Bergen Belsen landsmanshaft. As an only child, Menachem also spent time in the company of adults. He learned to listen, tell stories and outwit them.

Menachem Rosensaft’s moral voice goes beyond the responsibility we have as children of survivors to remember and educate. He felt the need to promote peace and a tolerant State of Israel. He felt he needed to bring to justice Nazi war criminals, to fight racism and bigotry wherever they raise their ugly heads, and to work towards the continuity of the Jewish people. In recent years Rosensaft has even begun to identify with his religious ancestry and has embraced a more traditional lifestyle. This is his way of bridging the gap to his own observant antecedents and is a way of identifying with his murdered relatives. If we keep their memory alive, it is as if they are somehow still with us.

Menachem Rosensaft grew up with survivors of Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen who taught him to respect all human beings. Rosensaft refused to use his knowledge as a basis for Jewish xenophobia. In fact, when Menachem’s father, the leader of the survivors of Bergen-Belsen, gave charity, he did not differentiate between Jewish or Catholic orphanages. To the elder Rosensaft, children were children.

“If you criticize the world for having been silent 50 years ago when Jews were being persecuted and murdered,” Rosensaft says, “we have no right to be silent when others are oppressed. In fact, any silence to the suffering of others legitimizes those who 50 years ago were silent themselves.”

In the post Holocaust world there is a paradox: those who could best empathize with the statelessness of the Palestinians the victims of Nazi persecution and their families felt that they had the most to lose by giving the Palestinians a homeland.

Abba Eban has said that the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians is not a conflict between right and wrong but a conflict between two rights. When one starts from this premise, the peace movement, according to Rosensaft, becomes the only possible avenue. “Those Jews who refuse to recognize that Palestinians are entitled to the same civil and human rights that we demand for ourselves, are at best xenophobic,” Rosensaft observed.

Even if the collective memory that has been passed down to the generation after the Holocaust has been that of the Jew as the eternal sufferer, the Jew as victim, we must go beyond that. Personally, I am one with Leon Wieseltier, who, when he watched the grudging handshake on the White House lawn, suggested that “collective memory need not contain only the memory of injustice, that justice, too, can be commemorated by a whole people, unto the generations.”

A moral message is actualized by means of a measure of moral risk and personal risk. The voice identified with the remembrance of the Holocaust had legitimate fears of Arafat and the Palestinian people. The Jewish world therefore needed permission from a moral voice of the Holocaust. When Menachem Rosensaft joined the group of American Jews who met with Yasser Arafat in Stockholm in December 1988, his presence was identified with the remembrance of the Holocaust when he introduced himself to Arafat.

When the opportunity presented itself, Rosensaft was confronted with a moral choice do the right thing, or abide by the Jewish community wide ban that forbade any meetings which would legitimize Arafat’s leadership of the Palestinians. Rosensaft, who at that time was also National President of the Labor Zionist Alliance, seized the opportunity to move the peace process forward without worrying about the impact on his own leadership in the Jewish community.

Perhaps we can look back at Stockholm and remember that small voice. It was trying to heal itself and move the Jewish people towards a more optimistic future for Jews and non Jews alike.

From Rosensaft’s personal experiences, we can see that the moral voice is derived from critical images of the Holocaust as they are transmitted to the Second Generation. In each case, some salient memory, conscious or unconscious, takes on a life of its own. One of the attorneys in the Office of Special Investigation who I interviewed and who wishes to remain anonymous, remembered that the first time she ever heard the word Nazis was while watching “The Three Stooges.” “I couldn’t have been more than 6,” she tells me. “Mo had a mustache and a swastika on, and I thought it was very funny.” She pauses, then adds, “But I didn’t understand it. I knew from the way my mother reacted, that it was very sad. I had a very loving gentle mother.”

While most children of Holocaust survivors have a generalized feeling about how they learned about the war, she has concrete memories of learning about the Nazi Party. “I watched a trial on television.” She does not remember if it was the Eichmann trial or a docudrama. What she does remember are the words of the victims who testified in court. She continues, “Women and men testified about the camps and medical experiments. I remember hearing the word Mengele.”

On a Sunday outing with her father after seeing the program, she spontaneously asked him about his life under the Third Reich. This is one very vivid memory of a conversation with my father. She was 14 or 15 and her brothers were some place else. She recounts that her father had been a refugee from Germany who managed to come to America in the late 30’s and joined the American armed forces.

She continues, “My dad had to drop pamphlets behind enemy lines. I don’t think he knew he would end up on front lines, screaming into loud speakers, doing dangerous stuff.

“While we were riding in the car, my father told me that he went into Dachau on April 30, 1945, the day after its liberation. Dachau was liberated April 29. He said, ‘When I got there…’ and he stopped. I looked at him and he just stopped talking and I saw that he was trying hard not to weep in front of me. But I didn’t say anything and to this day he has not told me what he saw. It is very hard to know that my father could not tell me.”

Of course, the Holocaust was never seriously talked about in Hebrew school or in public school. But at home it was a different story. Although her parents did not go into specific details discussion would focus on ten members of her family who died. “My mother had a big family and none of them survived. This one and this one and this one was killed. She would say, ‘Your cousin so and so and so and so was killed.’ It became clear eventually that we were talking about a fairly large number of people.”

She began to read about the Holocaust. In this young woman, reading these books generated a feeling of wanting to right a wrong. In the ’70s, there were serious allegations about Nazi war criminals who had immigrated (or, even worse, had been recruited to come) to America.

While in law school she read Wanted, Howard Blum’s book about the Nazis who came to the United States. She remembered thinking ” My own government allowed these people to come here.”

Documents were uncovered by the Justice Department, and in 1979, it established the Office of Special Investigations (OSI) at the behest of Congress and under the leadership of Brooklyn Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, who represented a neighborhood filled with Holocaust survivors. She read the article about OSI in the paper and knew immediately that this was her calling.

The evolution of a child’s commitment to moral action stemming from the parents’ ordeal does not require knowing all the details. For the woman at OSI, the critical images in childhood from television and the nonverbal communication from her father had an intense impact on her. In fact, it was not until her son did a school project on pilgrims that she learned how her father got out of Germany. She had no idea that she existed because of a Mont Blanc pen.

In 1938, when her father’s family was desperate to emigrate, the U.S. government rejected her grandmother’s application because her Polish birth certificate had her Hebrew names and her German papers carried her Germanized information. The bureaucrat said, “I don’t know if that’s your birth certificate. Get some certification from Poland.”

“They actually found a friendly man who went to this little town where my grandmother was born and saw the town clerk. And the clerk was eying his Mont Blanc pen and liked it, so this friendly man gave the pen to the clerk and got the necessary certification for my grandmother.”

The Second Generation attorney at OSI feels a moral imperative. She certainly does not see herself as someone who is steeped in revenge. While the moral voice of the children of survivors appears loudest and most moral when actively prosecuting Nazi war criminals and fighting for justice, moral conviction does not have to be so psychologically linked to the persecution.

A case in point is the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding that Rabbi Marc Schneier has established. The Foundation exists primarily to improve relations between Jews and other minority groups. On the surface it may not appear as if Rabbi Schneier is acting out of personal dedication to his family history. His father, Arthur, is a child survivor from Austria who established his own foundation, The Appeal of Conscience Foundation, which recognizes world leaders who exert moral courage. But it is racism that was at the core of Nazi ideology, and in order to avoid future holocausts to any group of people, society needs to have as its top priority the goals and values that are pursued by the Foundation.

Rabbi Schneier explains, “As a second generation person, I see that the demographics are changing in this country. Within 15 years the present minorities will constitute the majority in America. That means that African Americans, Latinos, Asians will be the dominant presence here. It is therefore incumbent upon the American Jewish community, which constitutes less than 2% of the American population, to reach out to them and try and look for lines of communication to further understanding.

Schneier continues, “The loss in my family clearly has motivated me and strengthened my convictions and the determination my commitment to Jewish life. People who don’t know me think I’m running for political office. People who really know me know that I love being a rabbi, and that’s where my commitment is.

“It comes from having grown up in my father’s home, from being the 18th generation of a very distinguished line of rabbis and understanding that we, the Second Generation have a historic responsibility. Our families could not save their own lives, but perhaps by remembering them, we can save and deepen our lives. That to me is the challenge of the second and third generation and not to give Hitler a posthumous victory.

Marc’s father saw his synagogue go up in flames on Kristallnacht. Ironically, our interview took place the day before Kristallnacht. Marc was thinking out loud, “If there is any anecdote of my father’s Holocaust experience that stands out in my mind it is that. Maybe subconsciously that caused me to commit to building a synagogue.” And maybe that’s why I responded the way I did to the African American churches burning.”

Susannah Heschel, grew up in the shadow of a great leader. Her father was the eminent Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. She saw her father risk his life for blacks in America. When he was called to join Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. for the famous Selma to Montgomery march, he hurriedly took a taxi to the airport after Shabbat, on a Saturday night in 1965. She remembers when he told his family, “I don’t know if I’ll be back.”

Rabbi Heschel, a Polish Jew, received his doctorate in philosophy at Humbolt University in February 1933, a month after Hitler came into power. For the next three years, Rabbi Heschel fought with bureaucrats in order to get his actual diploma. All around him older Jewish scholars were finding refuge. In 1937, his friend and colleague, Martin Buber, asked Rabbi Heschel to replace him as director of the Lerhaus in Frankfurt. Heschel stayed in Frankfurt for one year and was then arrested in the middle of the night with other “Ostjuden” and then was deported across the Polish border to be arrested again.

With help from his family, Heschel was reunited with his mother and a few remaining siblings. He had been unable to get a visa, but just six weeks before the Germans invaded he escaped to England and founded an institute similar to the Lehrhaus. In 1940 Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati offered him sanctuary and the position of assistant professor. When Heschel approached some influential American Jews to help him rescue other members of his immediate family, he was greeted with indifference and even hostility.

The rabbi’s theological writings and political responses were the way he guided the post Holocaust generation to heal itself. Still, his writings do not directly dwell on the Holocaust. At home, Susannah heard him speak about book burnings in Germany and going to a concert where Hitler was a guest. Everyone stood up and the rabbi left immediately. He spoke about going to a library run by Jesuits and asking the Jesuit priest, “Why aren’t you saying anything?” and they said, “If we protest they will close our library.”

Susannah was very cognizant of her father’s struggle with the university authorities to get his diploma, and ultimately, her career has evolved into an attempt to master her father’s futile struggles in Nazi Germany. Initially, her academic mark was as a Jewish feminist which she had been passionate about since the age of eight. Susanah Heschel as a graduate student in modern Jewish thought Susannah started making pilgrimages to Germany to use the archives for her research on Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, the Orthodox rabbi from Frankfurt who founded the neo Orthodox movement.

She began struggling with antisemitic German feminist theologians. Since then, she has been exposing German theologians and their antisemitic proclivities. Professor Heschel’s strong academic rigor, eloquence, and pioneering work on theological misuse to promote Hitler’s war against the Jews makes her an earnest force to respect. She has been training young German theology students to be aware of their own antisemitism. As a professor, Susannah Heschel is attempting to master what her father could not conquering antisemitism in the academic world. Like her father, she also addresses other, more global issues. She is a leading proponent of protecting our environment and employs traditional masoretic texts to find a way to get Jewish people do work on environmental issues. In the mid ’90s, Professor Heschel represented the Jewish community at the Rio de Janiero conference on the environment and later the Cairo conference on population.

Like Susannah Heschel, there is another second generation scholar that has emerged to confront the Germans, Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, author of Hitler’s Willing Executioners. Many historians have tackled the questions Goldhagen raises, but unlike the others, his narrative is driven by the atrocities committed. Each page is full of documentation of the abominations that Jews suffered at the hands of the Germans. Goldhagen elevates the discourse to a level of direct confrontation that broke the psychological atmosphere of denial in Germany. For example, a policeman walks a group of children to a pit where he will kill them. And Goldhagen asks, what is the policeman thinking as he is leading the children to be murdered?

Unlike previous theorists, Goldhagen concludes in a succinct dogmatic style that there is only one explanation for the ability of ordinary Germans to engage in such inhumane behavior — annihilationist antisemitism.

Goldhagen attributes the success of his book to his “intellectual authority” on this subject, rather than his moral authority as a second generation scholar. When it comes to creative and intellectual pursuits that are so directly linked to ones family history, such endeavors derive their spirit from the core self. One cannot separate the person from the work.

In my interview with Goldhagen he refused to discuss too many details of his childhood, because he wants his scholarly work to be judged on its analysis, rather than his personhood. Nevertheless, he grew up with a father who survived the German occupation in the Czernowitz ghetto with his nuclear family. He describes his father, a Harvard professor of German history as a “detached and penetrating scholar” who often discussed the Holocaust at home. As Goldhagen says, “it was part of the landscape.” At age ten Goldhagen lived in Munich with his family and since then has spent a considerable amount of time living and doing research in Germany.

Growing up with an immersion in Holocaust history has certainly influenced the route that Goldhagen’s intellectual pursuits have led him. But it did more than that. It left him thinking that he is intellectually superior to all scholars that have studied the Third Reich and the Final Solution of the Jews. Since Goldhagen is not an analysand of mine, I will refrain from making psychological interpretations about this moral stance that his analysis is the only correct explanation.

Moral convictions can become dangerous if one misuses them. Goldhagen says that everyone who has done research on the Holocaust has missed the point of annihilationist antisemitism. Goldhagen’s moral voice would have much more force if he would join others instead of denegrating and belittling the work of those who came before him. He has insulted and undermined the historic contributions of such scholars as Raul Hilberg, Yehudah Bauer, Michael Marrus, and Christopher Browning.

Christopher Browning, a respected senior historian, was the first to examine the archives of Police Battalion 101, which is the same data base for Goldhagen’s book. Goldhagen had easy access to the archival material after Browning struggled, with determination and tenacity, to have archives opened to researchers by reluctant German bureaucrats who were still trying to hide Germany’s role in mass murder. Browning’s analysis from retrospective interviews with some of the members of the battalion is more nuanced than Goldhagen’s when it explains the motivation of the killers.

In his book, Ordinary Men, Browning argues that the motivation of the Nazi policemen in Poland were not monolithic. His book, which may otherwise have gone unnoticed, was reviewed by Goldhagen while Goldhagen was working on a dissertation with the same topic Goldhagen’s review of Browning’s book generated an entire “conversation” in print on these issues. After doing my own research on rescuers of Jews, I tend to agree with Browning the behavior may be the same, but the underlying motives are complex and different for each individual.

Unlike Heschel, Goldhagen does not take a moral risk when asked questions about present-day German antisemitism. He undermined his own moral voice during interviews in Germany when he said that the antisemitism in Germany today has nothing to do with the antisemitism prior to 1945. This contradicts his whole premise that the antisemitism 100 years before 1933 has everything to do with the annihilation of the Jews, and that it did not start in 1933, but rather was endemic to German society.

Goldhagen lives in the past and is fearful of the retaliation of present-day German racists. To feel that way, you need to feel as if you are a member of a community. We know from basic sociological theories that evil ideologies cannot be fought alone. Goldhagen may have the support of the Holocaust survivor community and may be their moral voice to the children and grandchildren of the executioners, but he is not a part of the world of scholars whose lives have been devoted to uncovering and examining the Final Solution.

One does not have to fight Holocaust demons directly in order to use the moral voice. Issues unrelated to the past pop up everyday, along with new issues directly derived from the past. And children of survivors take a leading role in shaping the debate.

In the Soviet Jewry movement, children of survivors were at the forefront of saving fellow Jews. Rabbi Israel Singer General Secretary of the World Jewish Congress and Malcolm Hoenlein now executive director of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, each played leadership roles in risking their own life to save Jews in the former republics of the Soviet Union. Hundreds of other children of survivors seized the opportunity to act on their moral conscience. Many said to themselves, “no one was there for my parents when they needed rescuing, I don’t want future generations to say to me, where were you when Jews needed a life line?”

Israel Singer’s father sent one sister to America before the outbreak of World War II. Singer told me, “We had 113 immediate members of our family who were killed. They were killed in one day by the Einzassengruppen on the Polish Russian border in 1941. They never made it to the concentration camp. They were just shot into the pit, on Hoshana Rabah, 1941. We know of their death because one person survived. He was standing at the grave with a child and he was missed and he then hid in one place after another. He was reunited with the family by one of the Red Cross organizations.

One of Singer’s earliest memories is as a 3 year old standing at a kitchen table with 113 yahrzeit (memorial) candles that his grandmother lit on Hoshana Raba. The Brooklyn apartment was often full of survivors who gravitated towards his home because they did not have anyplace to sleep, and everybody lived in harmony. Nobody had any money. No one had anything. No one had any food. They would to sleep in the living room. Singer remembers asking, “What are these candles about?” He was told they represented his relatives. The patriach of the family was dragged from shul wearing his tallis. Buczacd was a town of 45,000 Jews including Nobel lureate Shai Agnon and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal.

“I made weddings for my three daughters, and the only rule my mother made was that every living relative should be invited to the wedding. Every child, every mechutin and every daughter and every baby. We invited almost no friends. We invited only the people who survived the war and reproduced. There are 348 indirect survivors of the five people who survived the war. Children of great grandchildren. We are in constant contact.

The other critical image that is etched in Rabbi Singer’s memory is the day Israel was declared a State. “I was aware that we were living in an ultra Orthodox neighborhood. My grandfather, who wore a bekishe and payos, had a seamstress sew a giant Israeli flag that was 5 stories tall, which covered the entire front of our house. We displayed it the day Israel became a State and for sometime thereafter. Ours was the only house in Williamsburg with an Israeli flag, and my classmates and the Hassidim would walk by our house and insult and attack that flag.

“My grandfather did not care, it was the vindication for the survivors.” He also remembers, a speech that was made by the Satmar Rebbe, an anti Zionist rebbe who lived in Williamsburg. “He said that Hakadosh Baruch Hou (God) has no right to test the Jewish people twice in one generation so closely; first, by killing us and then by giving us the State which shouldn’t be given to us until the days of the Messiah.” It was very disorienting for a religious child, yet the religious and the secular were so intermingled.

“It stuck with me all my life.”

Singer was a student and later an adjunct professor in Political Science. He also taught English at Yeshiva Torah Vodaath and law at Bar Ilan in Ramat Gan. He recalled, ” I was against the Vietnam War. I was in favor of human rights. I was involved in university struggles to take over the university during the sit ins in the ’60s. I was the only ‘yarmulke’ involved in civil rights struggles in those days a right wing Yeshiva student involved in left wing causes. But that brought me into a kind of public life, and it’s how I became involved in the struggle for Soviet Jewry, which is what brought me to the World Jewish Congress.

“As a representative of the WJC, I negotiated Mendolevitch’s release and the release of the other prisoners of conscience. the World Jewish Congress got all these prisoners out retail. I had gone to Russia earlier than most people. I went with my wife, under very strange auspices. Part of my motivation came from the Holocaust, the responsibility that I felt I had to do things for others that people did not do for my parents.”

“We were in strange places at strange times, and I must say we didn’t get out of some places too soon. So that is where I came in. I got involved in other causes and one of those causes was, of course, restitution It’s all part of the same thing. It is not a negative struggle. It is a positive struggle for Jews to become aware of who they are.

“I visited almost every country in which Jews live from Australia to Norway from Sweden to South Africa. I have met every different kind of survivor from Argentina to Russia. I met every different kind of survivor there who was blind, old, spoke only Yiddish, to Sephardic Jew that came from Salonika.

“I remember I was on my honeymoon, and my wife and I were sitting on a bus in a far away place and I slid over to a person who looked Jewish and began to speak to him. My wife told me if we visit one more cemetery, one more memorial, if I talk to one more old Jew, she will go back to the States and let me finish the honeymoon by myself.”

Another Second Generation leader in the Soviet Jewry movement is Malcolm Hoenlein. Hoenlien used to head the New York Jewish Community Relations Council, and in that capacity rented the electronic board in Times Square to honor the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr. on his birthday.

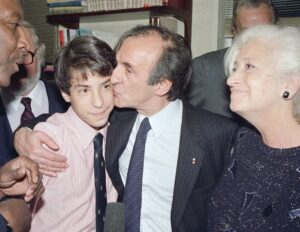

(Hoenlein is sitting in the middle with his head lowered)

Hoenlein’s parents were both German born. His father came from a small town in Bavaria and went to school in Wurzburg, then to the teacher’s seminary and university there. Malcolm’s father was arrested in the mid 30s, for the first time, and then left for Switzerland. In 1937, he returned to Germany for the High Holy Days and met his future wife.

The Nazis arrested him again, but he escaped because he had a rare pass to Switzerland where he taught skiing, Hebrew and English in St. Moritz, in Tzelarina, a school where people sent their children to escape. When he was forced to leave Switzerland, he traveled to Italy, France and Holland, arriving in the US in June 1940 on next to the last boat from Holland. His mother had arrived in 1938. His maternal grandmother never made it out, and neither did either of his paternal grandparents.

“We went to a rededication of the synagogue in the town my family came from. Although my father was already dead for several years, someone used his diagrams to rebuild the synagogue. He was an engineer and he never knew it.”

Hoenlein, the youngest of two siblings, was born in 1944. “My earliest recollections are of the Holocaust. While my parents did not talk about it until recently, I knew that they went into deep debt to get their parents out to Cuba. We found out later that their visas arrived a week after they were deported. And I know that what I do is strongly influenced by two things: One is the Holocaust and a commitment that a Jew should never be endangered and should be able to protect himself.

“The second I think is from my Jewish training. I have a strong sense of Klal Israel. I strongly believe in Jewish unity, not just as theory, but in practice. While I respect the differences that exist, I have spent my whole professional life working for umbrella organizations which seek to bring Jews together, to show that what we have in common far outweighs our differences.

“We didn’t have a big family. My parents had many friends who were the extended family. You always sensed that great void of not having grandparents and now as a grandfather, I see how it is different with my own children. We named our children after people who died in the Holocaust on both sides of the family. My granddaughter is named after my cousin who was killed. And my children carry on that feeling, all Jewishly involved and committed and oriented but also Klal Yisrael oriented.

“When I was 12 years old I went on the campaign trail with Adlai Stevenson. I was involved with activism on Israel and the Soviet Jewry movement from its very first days. I did one of the first programs on Soviet Jewry. I was arrested in the Soviet Union and have not been able to return there since. I began working on Soviet Jewry issues in 1964. Then I came to New York to head the Soviet Jewry Conference of New York.

“I think the driving force for us and for many others was the heroism of Soviet Jews. But if ‘Never Again’ was to mean anything and not just be a hollow phrase, we had to give it substance. We would not sit idly by. We have seen the difference in response to the plights of Ethiopian Jews, Syrian Jews. A lot of this is attributable to the State of Israel. Israel has taught us how to stand up. I think it is also manifested in the political activity and maturation of our community and our willingness to help other Jews.

“I don’t believe in power as an end in itself. It is what good you do with it, how you use it in the political process. That is the key to assuring the quality of life, the right to enjoy it and to use our ability to influence others.

In 1980 two sons of survivors, Sam Gejdenson from Conneticut and Ron Wyden from Oregon, both thirty one years old, were elected to serve the American people as Congressmen. Each uses the democratic process to promote equality for all people, to stop abuse of the environment, to deter nuclear buildup, and to open our shores to refugees. It is leaders such as Gejdenson and Wyden (now a senator) that instill hope in the positive use of governmental power, as opposed to its abuse in the Third Reich.

From Rabbi Abie Ingber, who is the director of the Hillel at the University of Cincinnati to Sam Norich, who was a student leader in Madison, Wisconsin, the Second Generations’ moral voices are also heard in local communities.

Today, Sam Norich, a director of the Commission on Israel Diaspora Relations established by the Israel Democracy Institute, a think tank established by Israeli Yossi Beilin, reconnects to his Jewish roots and the dreams destroyed in his parent’s birthplace.

Israel rekindled his passion for Judaism. His father had been active Zionist in his youth in Lodz and could not go to Palestine after the liberation because his wife and son were ill. For Norich, “politics was an actualization of community. That’s what attracted me to Israel, the idea that the place had been built by ‘we’.” Norich remembers walking in Tel Aviv with his father’s friend, a party comrade who worked in a construction company for 30 years. “He said: ‘We built that one in ’68, and we worked on that one in ’65.”

Norich could feel that it was part of a collective Jewish effort and that he was part of it. He felt reconnected with his parents when he became active in Jewish activities. He felt “it was an affirmation of my belonging to a political tradition I had come to independently. Once I got to Israel I discovered it had also been my father’s political tradition.” Learning his father’s political traditions modified and shaped Norich’s own.

What solidified Norich’s leadership were his day in day out activities in Madison, Wisconsin. “During my graduate years, I spent a huge proportion of my time on political activities. It simply became a habit. And with several other people, we founded Kibbutz Langdon, a co op in Madison, and I lived there for three years.”

The Jewish environment he chose to live in was defined not so much in religious terms but in social communal and political terms, although his religious consciousness developed in the course of living in this unusual American kibbutz.

At a chance meeting between Menachem Rosensaft and Ronald Lauder, Lauder told Rosensaft that if he ever wanted to do something meaningful with his life he should stop practicing international corporate litigation and come and see him. Several years ago, Rosensaft packed his attache case and now directs Lauder’s Jewish Rennaisance Foundation, which seeks to rebuilds contemporary Jewish life in Eastern and Central Europe.

Not until 1995 did Rosensaft set foot on Polish soil and visit the death place of his brother and grandparents. As Rosensaft works on reviving contemporary Jewish life in Poland, Suzannah Heschel is roaming the streets of Berlin, Frankfurt, and other German cities to continue the intellectual dialogues her father began with Hitler’s theologians.

Israel Singer follows the money stolen from the victims of the Holocaust wherever it leads. and some of those places are extremely interesting. Thanks to his efforts (and those of World Jewish Congress President, Edgar Bronfman Sr. and executive director Elan Steinberg, also a child of survivors) elderly survivors may soon be treated for medical and psychological conditions that could not be handled previously because of lack of funds. Perhaps some of them will be now able to die with dignity.

Malcolm Hoenlein continues to build bridges between Jews. Sam Norich tries to rework the Jewish Agency in Israel so that funds can be distributed equitably and effectively to all Jews living in Israel. Daniel Goldhagen moralizes to the Germans.

Members of the Second Generation who truly speak in a moral voice understand that the State of Israel, imperfect vessel that it is, needs to be included in the agenda. For most of the moral voices, the public and personal are intertwined. And so we have to set examples publicly, and privately. When one become a moral voice that represents a movement or a generation to separate the sacred from the profane is difficult. Leaders are scrutinized more closely than average people.

Elan Steinberg keeps his family background private, but he clearly is motivated by his parents’ fighting spirit when he relentlessly made the world aware of Prime Minister Kurt Waldheim’s Nazi past, or when he speaks on behalf of survivors’ stolen property and Swiss bank accounts. Steinberg’s succinct words say it all: “One of the earliest ways I related my parents’, hiding and escaping in the woods of Tarnopol, Poland was at the Passover Seder where we all have to see ourselves as if we came out of Egypt.” He paraphrased the Haggadah: “Whether we are learned, whether we know of the Torah whether we have studied, makes no difference whether or not you survived the Holocaust.” Steinberg says, “I am not sure where luck applies, I am not sure where circumstances apply, so in that sense I viewed myself as a miracle child and in a perverse kind of way our revenge against Hitler.”

Our obligation as sons and daughters of survivors is to create a world in which the traditional Jewish imperative of Tikkun-Olam is a paramount priority. Actively engaging in moral causes is one way to undo the sense of helplessness one feels in hearing about what happened to our parents. Although we cannot undo the pain and suffering they endured, we can master this defenselessness by speaking up against injustices today and helping oppressed people.

See also: