This paper was presented at the Women in the Holocaust: International Scientific Conference. 10 – 12 Oct 2023. Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory- Kraljice Natalije 45, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. See my blog post: Gender as a Dynamic in Women Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust.

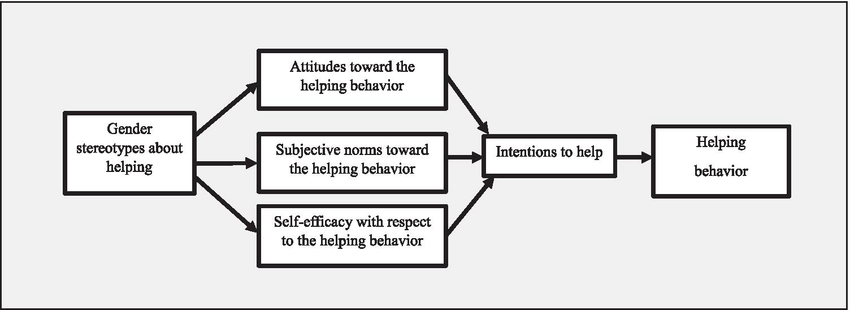

At the end of the twentieth century, popular culture in America was bombarded with emphasis on the psychological makeup of men and women as essentially different one from the other. Theories have gone as far as to say that men’s and women’s patterns of speaking are so different that they belong to different linguistic communities or cultures. When it comes to gender and helping, social-role theory stated that the male gender role fosters helping that is heroic and chivalrous, whereas the female gender role fosters helping that is nurturing and caring. A meta-analytic review essay in 1986 by Alice Eagly and Maureen Crowley concluded that women and men helped differently. Running throughout the various psychological literature, they described the assumption that women were more likely to help than men unless the situation was dangerous. In those cases, the presumption was that men were more likely to have the skills necessary to undertake risky rescues. It was also thought that masculinity and accompanying notions of chivalry led men to offer help more readily to strangers. The female gender role, on the other hand, motivated women to acts of caring for others.1

In 2004, the psychological literature shows a theoretical shift towards a gender similarities hypothesis.2 And in fact, Alice Eagly writing a review essay with Selwyn Becker has reformulated her earlier understanding of helping. This time, Eagly studied heroic behavior, including an analysis of rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust based on existing data. Becker and Eagly conclude that there are almost a similar number of men and women who were involved in risking their lives to save Jews. Thus, the notion that men are more readily involved in dangerous helping behavior was not substantiated.3

The Rescuer Project

My own research on rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust concurs with the gender similarities hypothesis. In the early 1980s I embarked on an international social-psychological study of why non-Jews risked their lives to save Jews during the Third Reich in German-occupied Europe. I interviewed more than three hundred Chasidei Umot Haolam, Righteous Among the Nations of the World, non-Jews who were designated by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and archives, as individuals who did not take any rewards, monetary or otherwise, for risking their lives to save Jews. I also interviewed Jewish adults and children who were rescued; in some cases the victim-rescuer pairs participated in the study.

I found rescuing behavior to be infinitely more complex and varied than these stereotypical, gender-based assumptions with men as risk-takers and women as nurturing and caring helpers. A number of factors increased the likelihood that an individual—male or female—would help: having a personality that is independent, a heightened sense of trust in one’s competency, an inclination toward risk-taking, emotional involvement with Jews, special abilities, available resources, various situational elements, ability to confront complex moral questions, and ultimately a supportive social milieu. In fact, my research leads away from the traditional thinking. As social psychologist Carol Tavris has said: “We can think about the influence of gender without resorting to false polarities”.4

Moral Reasoning Based on Gender

Freud recognized that “character traits which critics of every epoch have brought up against women—that they show less sense of justice than men…that they are more often influenced in their judgments by feelings of affection or hostility—all these would be amply accounted for by the modification in the formation of their super-ego.” But “as a result of their bisexual disposition and of cross-inheritance, they combine in themselves both masculinity and femininity which remain theoretical constructions of uncertain content”.5Nevertheless, distinctions have been made.

Piaget, using hypothetical dilemmas to measure moral judgment in children, found that boys, unlike girls, tended toward organized games with elaborate rules. Therefore he concluded that boys were more concerned with justice than girls. It was the fairness and impartial, abstract justice of rules that Freud, Piaget, and others believed was the essence of an individual’s morality.

In the 1960s, Harvard University psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg, refined Piaget’s early work by charting moral development through six distinct stages, each one more advanced and mature than the one before. Kohlberg created hypothetical moral judgment stories. For example, your wife is very sick and will die unless she gets a very expensive medicine that you cannot afford. Should you rob the drugstore? From the answers, Kohlberg concluded that individuals at Stage Six, the highest level of moral reasoning, were those who had the ability to consult their conscience and act on universal ethical principles. At that level, an individual was motivated by abstract, ideological beliefs of justice. He asks himself, “What should I consider fair if I were in the other person’s place?” and proceeded from there. Later Kohlberg backed away from this strict hierarchy, acknowledging that Stages Four, Five and Six are also “alternative types of mature responses”.6

In the 1970s, psychologist Carol Gilligan challenged the prevailing views of psychological development, which up to that time had been based almost entirely on research with men. Gilligan agreed with Freud that women and men differ in what they regard as “clinically normal”, but she maintained that women’s moral reasoning was not faulty; it was simply different.7

Gilligan argued that there are two kinds of morality that stem from two different kinds of motivation. One is a morality based on impartial idea of justice, and the other is a morality based on compassion and care. Gilligan believed that the value of caring in human relationships, which coincides with Kohlberg’s Stage Three, is as important as justice (Stage Six). What matters ultimately to women, Gilligan found, is being responsive to human feelings—that is, judging by “hearing a human voice”. A woman’s need to make and maintain interpersonal connections plays as important a role in moral decision-making as fairness does in the understanding of rights and rules. When facing a moral decision, women do not think about what is fair so much as “who will be hurt the least”. According to Gilligan, compassion for others is not a sign of weakness or a symptom of neurotic dependency but another dimension of moral development.

Gilligan was the first theorist to place caring and justice on an equal footing. To her, morality was not an abstract concept of right and wrong to be charted in a classroom setting. Justice and mercy, responsibility and care, were learned through human interaction. This morality of care implied empathizing with another’s distress and actively offering support and aid.

Female and Male Morality Applied to Holocaust Rescuers

Gilligan’s notions of “female” morality as contrasted with “male” morality would lead one to expect that emotional-moral rescuers (morality based on compassion for Jews) and Judeophiles (morality based on emotional attachment to Jews) would be mostly women, and network rescuers (motivated by anti-Nazi ideology) would be male. This is not what I found in my discussions with rescuers from all walks of life. Despite their different motivations, men and women were equally represented in various groups based on why these non-Jews risked their lives to save Jews during the Shoah.8

Rescuers were unable to articulate all the reasons they participated in altruistic acts. Motivations were complex and real situations may have changed motivation over time of the rescuing relationship, many of which lasted years. In tracking an individual’s initial rescue effort, five distinct patterns emerged: moral—people who were prompted to rescue Jews by thoughts or feelings of conscience; Judeophiles—people who felt a special relationship to individual Jews or who felt a closeness to the Jewish people as a whole; network—people fueled by anti-Nazi ideology, joining others who were politically opposed to the Third Reich; concerned professionals—people such as doctors or social workers who held jobs in which helping was a natural and logical extension; and children—who started helping rescue Jews at the behest of their families.

Rescuers’ morality was of three types: ideological, religious, and emotional. Ideological morality was based on rescuers’ ethical beliefs and notions of justice. A congruence between moral beliefs and actions had always been a part of their lives. They stood up for their beliefs; and so when they were asked to help, they did. They were more likely than any other moral type to be politically involved. Religious-moral rescuers described their sense of right and wrong in religious rather than ethical terms. Their morality was based on tenets of “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. Emotional-moral rescuers felt a compassion for victims of Nazi persecution that compelled them to help. Emotional-moral rescuers were the rarest of the moral rescuers. They responded to the helping situation out of compassion and pity, not just from an ideological sense of right and wrong. Theirs was a morality based on caring and responsibility, the same morality that now New York University psychologist Carol Gilligan celebrated in her groundbreaking book, In a Different Voice. Gilligan proposed that a morality based on compassion and concern for others was more prevalent among women than among men.

I saw, in my research, the two kinds of moral reasoning Gilligan describes. But the link between gender and reasoning style was not as strong as Gilligan’s analysis suggested it would be. Both men and women showed morality based on caring and attachment. Both men and women had emotional responses to the plight of the Jews. Both men and women came to the aid of victims through an outraged sense of justice.

Women undertook dangerous missions. Women were involved in high-risk activities like slipping Jews past German patrols and guiding them safely across the border. On the other hand, men were motivated by feelings of compassion and pity, with some still emotionally shaken by their experiences, weeping unashamedly as they relived that time.

In the course of my research and work at the Anti Defamation League’s Jewish Foundation for Christian Rescuers9, which I founded along with Rabbi Harold Schulweis (1986), I talked with men who were so emotionally affected by what they saw that they turned their lives upside down, jeopardizing everything in order to save Jews. The story of Alexander Roslan was certainly the most dramatic example of this. The sight of the bodies of children in the Warsaw ghetto so affected Roslan that he risked his life, fortune, and emotional stability to save Jacob, Sholom, and David. Roslan characterized those scenes he witnessed in the ghetto as the most difficult moments for him during the war. “You can’t eat”, he remembered. “You can’t sleep. If you see things like that, you can get sick”. It was this emotional reaction that transformed Roslan into a rescuer.

Roslan’s love for Jacob, Sholom, and David transcended any cognitive moral imperatives of fairness or justice. He nurtured three youngsters even more than his wife did, who could never completely overcome her fears of discovery and death. Similarly, the responsibility for the emotional care and welfare of the two Jewish children sheltered with the Stenekeses fell on John Stenekes rather than his wife Berta. Even at the start, when the children were staying with Stenekes’ sister, John kept a paternal eye on Jack and Anna and gave them bakery treats when they came around. It was he who offered to hide the children when his sister lost her nerve and planned to put them into a hotel. John Stenekes empathized with their situation, took to heart their need, and felt compelled to act. He was the one who broke the news to his wife that the two children who played with their baby were Jewish and that unless they took them in, the children would be killed. Berta Stenekes agreed to shelter them, but John shouldered the responsibility for looking after them.10

The work of University of Massachusetts social psychologist Ervin Staub shows similar findings11. Staub found that gender did not necessarily predispose a person to be caring. Staub, who as a six-year-old child was rescued in Budapest by Raoul Wallenberg, developed a scale to identify people with altruistic natures. Those who scored high on his scale were more concerned with the welfare of others. Staub found both men and women who scored high. Staub concluded that while there may be a tendency for women to be compassionate and caring, this was largely due to early socialization, and men were just as capable of having such feelings and acting on them. It is the development of caring and responsibility in boys that enables them to be just as kind as women.

While male rescuers sometimes used Gilligan’s “female voice”, women frequently displayed temperaments and attitudes that Freud attributed to his model of “moral man”. In women such as Marion van Binsbergen Pritchard and Louisa Streenstra, Hitler’s philosophy and Nazi policies triggered deep-seated revulsion. They were outraged by seeing justice so perverted. Witnessing German soldiers carelessly tossing Jewish children into trucks and watching as two passerby tried to stop them left Dutch rescuer Marion van Binsbergen Pritchard shaking with anger. Louisa Steenstra’s anger at the German bombing of Rotterdam and the unjust killing of 30,000 people in one day shocked her into action. “When you hear that, how can you not act?” she said. “I couldn’t stand it. I hated the Germans”. This anger consumed her and consumes her still. Anti-Nazi anger and rage at the human race for its proclivity for cruelty were themes to which she returned time and again in her conversation with me.

Recent research has further undermined the notion that men and women differ appreciably in their moral reasoning, or that women have a permanently different voice because of their early closeness to their mothers. Anne Colby and William Damon found little scientific support for Gilligan’s claims for general gender-based distinctions. They concluded that “to the extent that differences of this sort do exist, there is no evidence whatsoever that they are due to early and irreversible emotional experiences between mother and child.12

But Gilligan’s research was not the only body of work which led me to believe that there might be differences in the way men and women reacted to Hitler’s war against the Jews. Philip Friedman, one of the first historians to write about the Holocaust rescuers, suggested that non-Jewish women may have been more sensitive than non-Jewish men to the plight of Jews. Friedman hypothesized that women’s nurturing and caring natures might have made them a soft touch, especially when those in danger were children. Women might have been “more easily moved by their emotions and thought less of the consequences”.13

Frances Henry, a Canadian anthropologist who studied a Bavarian community whose pseudonym is Sonderburg, reported that in her study more women than men helped. Henry, whose grandparents and ten other Jews living in Sonderburg were helped by locals for three years until their eventual discovery and deportation, felt that this was because most of the help involved giving the fugitives housing and food. Unlike the administrative tasks of obtaining forged documents or lining up escape routes, food and domestic arrangements were the traditional province of women. This same point was made by Pierre Sauvage, the filmmaker who as a boy was saved by rescuers in Le Chambon. Sauvage noted that most often it was the women, who were at home most of the day and were in charge of the domestic arrangements, who were the first ones to be approached to take a stranger into their homes. That first important critical decision, to help or not, was theirs to make. In Sauvage’s mind, the women of Le Chambon were the “backbone” of that community’s rescue effort.14

Yet an early study by German political scientist Manfred Wolfson contradicts Henry’s findings and Sauvage’s observations. In 1966, Wolfson who was working in the United States, solicited letters and other documents from seventy Germans who helped Jews between 1938 and 1945. He concluded that more men than women helped.15

Female Rescuers Defy Stereotype

Running through all these various inquiries was the assumption, sometimes implicit, sometimes overt, that in dangerous situations men would be more likely to help. I too assumed that women would undertake less physically taxing or hazardous tasks and leave the heroics to men.

Time and again I was proven wrong. Women told of how they had acted as decoys, couriers, double agents, and border runners. Women such as Czechoslovakian historian Vera Laska were an integral part of both resistance and rescue work. Laska was a Czech resistance fighter who also led Jews and other fugitive to safety in Yugoslavia. German patrols made these border crossings extremely dangerous. Nonetheless, men and women such as Laska and John Weidner gambled that their wits and luck would see them through.

Polish resister and rescuer Jan Karski felt that women were better suited for undercover or conspiratorial work because they were quicker to perceive danger, less inclined to risky bluffing, and more optimistic of the outcome. In particular, he praised the role of the network liaison woman or courier, whose job it was to warn of impeding raids, move the hunted from house to house, and carry information from one network member to another. Marc Donadille, the French Protestant minister who led the Cévennes escape network, years later paid public tribute to such women:

I want to praise the operator in the post office in Saint-Privat, whose name I don’t remember. She was Catholic, but shared our feelings and our concerns. One day she said, “The phone calls between the police at Florac and the brigade at Saint-Germain come through me. I can pass that information on to you”.

Then, rather than relay information, she simply hooked my line into these conversations so I could listen directly… Then she told me that she had orders to intercept my mail. “I’ll put your mail aside and you can get it at night from my house. Then you can remove the compromising letters and I will send [the rest] on. This we did regularly.16

Joutard, P., Poujol, J., & Cabanel, P. (eds.). 1987

The telephone operator was playing a very risky and dangerous game. Had the Nazis caught her, she would have faced the same possibility of imprisonment, torture, or execution as Donadille or any other male resistance worker. She did have, however, one advantage: officials in some countries, particularly the Netherlands, were sometimes loath to pronounce a death sentence on a woman. A woman who was caught often stood a better chance of being sent to a concentration camp than being summarily executed. Hetty Dutihl Voûte, who was caught for her illegal Utrecht children’s rescue work and sent to Ravensbrück, thought that had she been a man, the Nazis would have shot her.

Given the opportunity, women proved to be good spies, smugglers, and saboteurs. Yet their deeds were largely overlooked. In the postwar celebration of men’s daring deeds, the quiet bravery of women was ignored. The traditional hero was a swashbuckling male. And heroes who did not fit that model were ignored. Movies and made-for-television features portrayed male heroes. Women, if they had any rescue or military role at all, were cast in minor roles.

In building a new, postwar national identity, heroes needed to be larger than life, and so military leaders such as Charles de Gaulle and those active in armed resistance were glorified. The medals and ceremonies recognized military heroes, not the milkman who left an extra bottle of milk for a family sheltering Jews, or the nurse who put a sign in a hospital room “Quarantine” “Do Not Enter” so that the SS would think twice about entering the room to deport a Jewish patient.

World War II represented an opportunity for women to escape their normal domestic concerns and express their anti-Nazi outrage by taking action in behalf of a just cause. “We think of war as a male activity and value,” social psychologist Carol Tarvis noted, “but war has always given even noncombatant women an escape from domestic confinement—the exhilaration of a public identity—and a chance to play a heroic role usually denied them in their private lives”.17

The chance to escape normal boundaries and become an important part of a larger cause sometimes gave women the courage they needed to undertake risky ventures.

Certainly this was the case with Anje Roos, a woman whose implacable opposition to Nazism grew from small acts of kindness.

In 1940, when the Germans took over Holland, Anje Roos had nearly completed her training as a psychiatric nurse. Roos had no illusions about Hitler’s intentions. Her parents, who lived in Alkmaar, a town twenty miles north of Amsterdam, had told her and her seven brothers and sisters often enough that the Führer meant what he said. He aimed to rid the world of the infirm and the racially impure and rule the world. With the Germans now in charge, Roos knew psychiatric nursing did not have much of a future. She changed directions and began to study to be a midwife.

Soon after the Germans took over, they banned Jews from professional employment. Jewish doctors and nurses were no longer permitted to work at the hospital. Roos, who in addition to taking courses at the hospital worked in the tuberculosis ward, was outraged. The patients were too. Together with the head nurse, Roos wrote a petition asking that the order be withdrawn. All the patients signed it, and it was sent off to the Austrian governor in charge of the occupation. It proved to be a futile effort, but for Roos and the patients it was, nonetheless, a healthy tonic. “It didn’t help; no reply ever came. But there was a kind of elevation around the ward that they did something,” Roos explained. “It was important for them as well as for us to do something—to demonstrate—to tell them we didn’t like it and we were angry”.

In the spring of 1941, Roos completed her training and rented a house in Amsterdam with three other nurses. Her roommates had many Jewish friends, and on Fridays it became the custom for Roos and her roommates to buy goods for them that they were not permitted to purchase. Through these new friends and through the Jewish family she worked for as a baby nurse, Roos’s awareness of the plight of the Jews increased. She felt close to her employers and knew the dangerousness of their situation. The precariousness of their position became evident one day when she answered a knock on the door. It was the Gestapo hunting for Jews to deport. With the family safely out of sight, she faced the Gestapo and told them no Jews were there. They had already been arrested. “You do such wonderful work,” she told them sarcastically.

With little time to lose, Roos arranged for the family to travel to Utrecht and be hidden in a home there. Later she learned the family had been captured by the Germans when they naively went for a walk in town. Roos returned to work at the hospital, but it was clear to her and her friends that the Jewish situation in Amsterdam was rapidly deteriorating. When Jewish friends who belonged to the Palestine Pioneer movement asked her for help, she was ready, even eager. Her anti-Nazi rage needed an outlet.

By day, Roos bicycled around town hiding Jewish children and delivering documents, food, and money to those in hiding. By night she worked at the hospital, where, along with her nurse friends, she stole as many drugs and hospital supplies for the underground as she could. Her duties for the Palestine Pioneers, a network affiliated with the Dutch underground Westerweel Group, were arduous and not always predictable. She was frequently late for work or absent altogether. Her nursing supervisor told her to shape up or she would be fired. Roos did not know what to do. Both jobs were important to her, but she did not know how she could manage both. So she turned to her parents for advice. As she recalled, her parents told her, “If you want to help the Jews—and you should—then do that and don’t work with the nurses anymore. They don’t need you there. They need you with the Pioneers”.

Her parents’ blessings broke Roos’s last restraints. A new persona, free of the ordinary expectations of female behavior, was born. She immersed herself in rescue work. She involved her whole family. Roos picked up Jews and transported them to her parents’ house. From there she would find safe houses for them in other parts of northern Holland. Through friends and Christian religious circles, she found safe places for all her charges.

The Palestine Pioneers was only one of several networks for whom Roos worked. Along with one of her brothers, who was a police officer, Roos joined the Arondius Group, an underground sabotage organization. Members of the group, Jews and non-Jews were on the Germans’ most-wanted list. In March 1943, the Arondius Group decided to raid the Nazi registration office to burn the files that held the names and addresses of all the Jews in Amsterdam. They thought that without such information the Nazis would find it more difficult to round up and deport the Jews.

Dressed like police officers, the saboteurs overpowered the night watchman and set the place on fire. The mission was a success, but their victory was short-lived. Careless talk among network members gave them away, and a month later Roos, her brother, and the others involved in the raid were arrested. Roos’s brother and twelve other Arondius members were tried and shot. Roos was sentenced to serve one year of hard labor in Ravensbrück.

After a year and a month, Roos came home. She was weak, painfully thin, and ill with tuberculosis. That slowed but did not stop her. As soon as she was physically able, she rejoined her friends and the Amsterdam resistance. She worked as a courier for an underground newspaper, distributing news and false identification papers as needed.

Roos does not fit the implicit social-gender role of a female rescuer. Her rescuer self was not that of a resourceful, home-based caretaker. While she and her roommates hid fugitives in their house, most of her rescue activities took place outside the home. Her rescuer self was adventurous, daring, and bold. This kind of rescue is alleged to describe a male social-gender role. While many women in networks were called upon to help in domestic chores, Roos had many other women in her network and in others whose rescue activities ignore social-gender roles.

The existence of heroic women seemingly contradicts other social-psychological research, which suggests that daredevil women would be rare. In experimental situations requiring one-time heroic actions (such as jumping into a river to save a drowning person), researchers have found that men tend to be more responsive. Women are more apt to size up the situation as too dangerous to attempt to do anything.

During the Shoah, women confronted a myriad of situations—not a one-time experience—that required heroic interventions. By “heroic” I mean deliberate actions, which place the person in sharp danger. Without question, rescuers who hid Jews in their homes were heroic people; their actions, however, were not. They had all the comforts and familiarity of home and neighborhood. They did not repeatedly seek dangerous missions. Heroic rescues did. From one night to the next, Roos never knew where she would sleep. Laska did not even know what country she would be in the following day.

The work of Kay Deaux, social psychologist at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, helps explain the apparent gap between my findings and the work of others. Deaux found that skill level matters in moral acts as well as in more commonplace ones. For instance, a woman who was a good swimmer would be just as likely to jump into a river to save a drowning person as a man who was a good swimmer. The key variable is swimming ability, not gender or morality. Women did not avoid danger or hang back from risk per se. If women felt they had the skills useful in a particular situation, they helped.18

Much of the time skills are divided along stereotypical gender lines. Fifty years ago, most women were full-time housewives and mothers. If they worked outside the home, they were most likely to be factory workers and farmers or to hold jobs in traditional women’s fields of teaching, nursing, or social work. Very few women were printers, mechanics, or captains of industry. In wartime resistance activities these distinctions between men and women were not absolute. There were women forgers, saboteurs, and money launderers. But for the most part, women undertook or were assigned rescue tasks that centered on their household and child-rearing skills.

Stereotypical Women’s Role in Rescue

At home, women took responsibility for the people they were hiding. It was difficult work. Quarters were often cramped, nerves frayed, and hunger constant. Each simple task, from hanging out laundry to emptying chamber pots, contained the possibility that someone would spot something suspicious and report it to the authorities. It was left to one member of the household to keep things running and to keep people’s spirits up in the process. That job usually, but not always, fell to the woman of the house.

The Voses, for example, divided up the chores. Aart Vos was responsible for the house’s outside liaisons with the underground and obtaining food, while Johtje was in charge of the household. Each of them had a dangerous task. Aart traveled all over the countryside on his motorbike, calling on his dairy-farm contacts to scrape up supplies to feed his burgeoning household. He knew that anyone caught transporting food over a road was subject to arrest.

Johtje Vos oversaw the domestic arrangements of the household. She acted as a combination traffic controller, cook, arbitrator, psychoanalyst, and entertainer. She hosted candlelit parties for which the fugitives dressed up in clothes borrowed from one another. She led the children in games, such as “Who remembers what a banana looks like?” Johtje did anything she could think of to distract them from dwelling on their discomfort and fears. Aart Vos realized how demanding a job his wife had:

We had thirty-six people hiding in our house at one time. When you have a home, not a big one, and you have it filled up with Jewish people coming in and out the whole day, every day, not for a week but for four or five years, you can’t understand what that takes out of a woman. I was out on my bicycle, but she had to keep everyone together.

Eva Fogelman. Conscience and Courage. p. 48

When the Nazis suspected the Voses of possessing the stamps to forge illegal documents, it was Johtje who was left to deal with the Gestapo and connive a way out of a lethal situation. Her ability to act took charge, bluffing, stalling, and finally strategizing their charges’ according to sociologist Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, show that “behavior that we link to gender depends more on what an individual is doing and needs to do than on his or her biological sex”.19

At times, however, the roles of men and women in rescue activities were determined by gender stereotypes. For example, when children needed to be transported, hidden, and cared for, women usually saw to it. Many of the networks that were engaged primarily in the rescue of children were headed by women. Irena Sendlerowa in Poland, Anje Roos Geerling and Hetty Dutihl Voûte in Holland, and Andree Guelen Herscovici in Belgium led their country’s efforts to save children. Those children’s rescue networks not headed by women, like NV (short for Naamloze Venootschap, the Dutch equivalent of “limited company,” or “Ltd.”) and the Piet Meerburg, boasted an overwhelmingly female membership.

But for the most part, it was women who led or rallied behind efforts to save children. There were a number of reasons for this. To some extent, women were more actively called upon than men to rescue children because women’s efforts were perceived as having a greater probability of a safe outcome. Networks assigned tasks according to skills, and most male network leaders assumed women were better suited to care for children. Jewish parents made the same association. They were more likely to trust the safekeeping of their children to a Christian woman than to a Christian man. Among Jewish parents, nannies were the rescuers of choice. When that was not an option, parents looked for the next-best thing, a single young woman. A couple was not desirable. Jewish parents feared a couple would try to convert their children and that a couple, who represented a ready-made family, would be more reluctant to return their children to them after the war.

Network leaders knew that and assigned the job of prying Jewish children from their parents to women. Belgian schoolteacher Andree Guelen Herscovici, for example, was recruited by the Comite de Defense des Juifs (CDJ) to call on Jewish parents and lead their children to safe houses. The Gestapo had a list of all the Jews who still lived at their official addresses, and the CDJ had the same list. It became a race between Herscovici and the Gestapo over who would get there first.

Clark University historian Deborah Dwork, who interviewed rescuers of children in the NV and Piet Meerburg networks, found that women couriers were the mainstays of both operations. The groups, most of whose members were university students, specialized in saving children because they felt their age would undermine their authority and effectiveness with older victims. Piet Meerburg, the student who formed the network, told Dwork why 90 percent of his members were women: “It was much more suspicious for a boy of twenty to travel with a child than a girl. It was absolutely a big difference. We went to fetch the children from the crèche [nursery] together, but then the woman student accompanied them on the train to Friesland and Limburg”.20

There was still one other role that women, and only women, played in the rescue efforts, and that was the role of “single mother”. Nannies, friends of the family, and even strangers—often found through network contacts—were asked by Jewish parents or by intermediaries to shelter a child. Those who agreed needed to make up a story to cover the sudden arrival of a baby or a child. Exactly what the cover story was and how believable it was depended on the individual and the circumstances. Many young women moved to other villages and posed as married women whose husbands were at the front.

Still others claimed the child was a relative whose parents had been killed in a bombing raid. Whatever cover the rescuer self-scripted, the person had to act it convincingly. Husbands, wedding days, tragic war events—a whole family album of lies—had to be fabricated to lend an air of authenticity. No man could ever get too close. Secrets kept them on their guard at all times. These “mothers” did not want to place their own family and friends in danger. The other, they dared not trust.

Single mothers created stories that were inventive, daring, and frequently unbelievable. Relatives and old friends doubted the existence of a husband they had never heard of or seen. The suspicion among neighbors, the gossip around town, labeled them unwed mothers. All of a sudden, they were young women of uncertain reputations who were no longer desirable as potential wives. In a Catholic country like Poland, such whisperings were devastating. These women were considered social outcasts. To escape the gossip and any suspicions of the truth, they moved to another village. When the whisperings and suspicions started up again, they moved on.

These women willingly paid a huge personal price. Their reasons were no different from anyone else’s. Like men and other women rescuers, they faced danger and gambled their lives to alleviate suffering and satisfy their sense of justice. What they did and how they did it reflected their individual personalities, talents, and social roles. Women helped in typical social-gender roles, such as taking care of children, as well as in roles that defied or ignored social-gender expectations of others. In the extreme situation, one never knows how he or she will react in a particular moment in time. In the end, Carol Gilligan’s “different voice “can be a motivating force for both men and women. What is expressed is a shared voice of common decency and humanity.

- Eagly, A. H., & Crowley, M. 1986. Gender and helping behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100 (3), 283-308. The review article also mentioned that there was a slight tendency for women to help women more than men to help women

- Shibley Hyde, J. 2005. The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60 (6), 581-592.

- Becker, S.W., & Eagly, A. H. 2004. The heroism of women and men. American Psychologist, 5, 163–178.

- Tavris, C. 1992. The mismeasure of women. Why women are not the better sex or the opposite sex. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 289.

- Freud, S. 1925. Some psychical consequences of the anatomical distinctions between the sexes. Standard Edition, 19:257.

- Kohlberg, l. 1969. The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In D.A. Goslin (ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chicago: Rand McNally. pp. 347-480.

- Gilligan, C. 1981. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fogelman, E. 1987. The rescuers: A socio-psychological study of altruistic behavior during the Nazi era. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Fogelman, E. 1990. What motivated the rescuers? Dimensions: A Journal of Holocaust Studies, 5 (3), 8-11. Fogelman, E. 1994. Conscience and Courage: Rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday.

- The ADL’s Jewish Foundation for Christian Rescuers, now the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous. More than 1,700 rescuers are receiving monthly financial stipends to assist them in their waning years in 26 different countries.

- My findings mirror those of sociologist Barbara Risman and Lenard Kaye and Jeffrey Applegate. Risman compared the personality traits of single fathers, single mothers, and married parents. She found that single men who had custody exhibited personality traits—specifically nurturing and caring –that were much more like mothers than married fathers. Similarly, in 1990 psychologists Lenard Kaye and Jeffrey Applegate, who studied 150 men who were spending sixty hours a week caring for their ailing parents or spouses, found that these men provided just as much emotional support as women traditionally do. The obligation of providing care customarily falls to women, but when men do it, they do it just as well and lovingly. Risman, B.J. 1987. Intimate relationships from a microstructural perspective: Men who mother. Gender and Society, 1, 6-32. Kay, L. W., & Applegate, J.S. 1990. Men as elder caregivers: A response to changing families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60, 86-95.

- Staub, E. 1978. Positive social behavior and morality. New York: Academic Press. vol. 1, pp. 39-73.

- Colby, A., & Damon, W. 1987. Listening in a different voice: A review of Gilligan’s In a Different Voice. In M.R, Walsh (ed.), The Psychology of Women: Ongoing Debates. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 327

- Friedman, P. 1955. Righteous Gentiles in the Nazi era. In A. J. Friedman (ed.), Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. pp. 409-421

- Sauvage, P. 1986. Ten questions. In: C. Rittner and S. Meyers (eds.). The Courage to Care. New York: New York University Press. p. 137.

- Wolfson, M. 1970, April. The subculture of freedom: Some people will not. Paper presented at the regional meeting of the Western Political Science Association, Sacramento, CA.

- Joutard, P., Poujol, J., & Cabanel, P. (eds.). 1987. Cevennes: Terre de refuge 1940-1944. Montpellier: Presses du Languedoc/Club Cevenol. pp.257-258.

- Tarvis, p. 68.

- Deaux, K. 1976. The behavior of women and Men. Monterey: Brooks/Cole Publishing Compant.

- Fuchs Epstein, C. 1988. Deceptive distinctions. New Haven, London and New York: Yale University Press, Russell Sage Foundation. p. 99.

- Dwork, D. 1991. Children with a star. New Have: Yale University Press. p. 53.