When my father died, Elie Wiesel came to my home to make a shiva call.

The first question he asked, “Did your father write down his story?”

This question continues to haunt me every day as new questions keep popping up. My father was killed by a van that swerved too quickly from around the corner as he was crossing the street near his home in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, to buy fruits and vegetables. My mother at the time was a few blocks away swimming at the local Y. Luckily my father, who had just gotten out of his car, had a driver’s license on him. The ambulance arrived and took my father to a local hospital and the police drove to my parents’ house and knocked on a neighbor’s door who guessed that my mother was probably at the “Y” swimming, as she was wont to do almost daily.

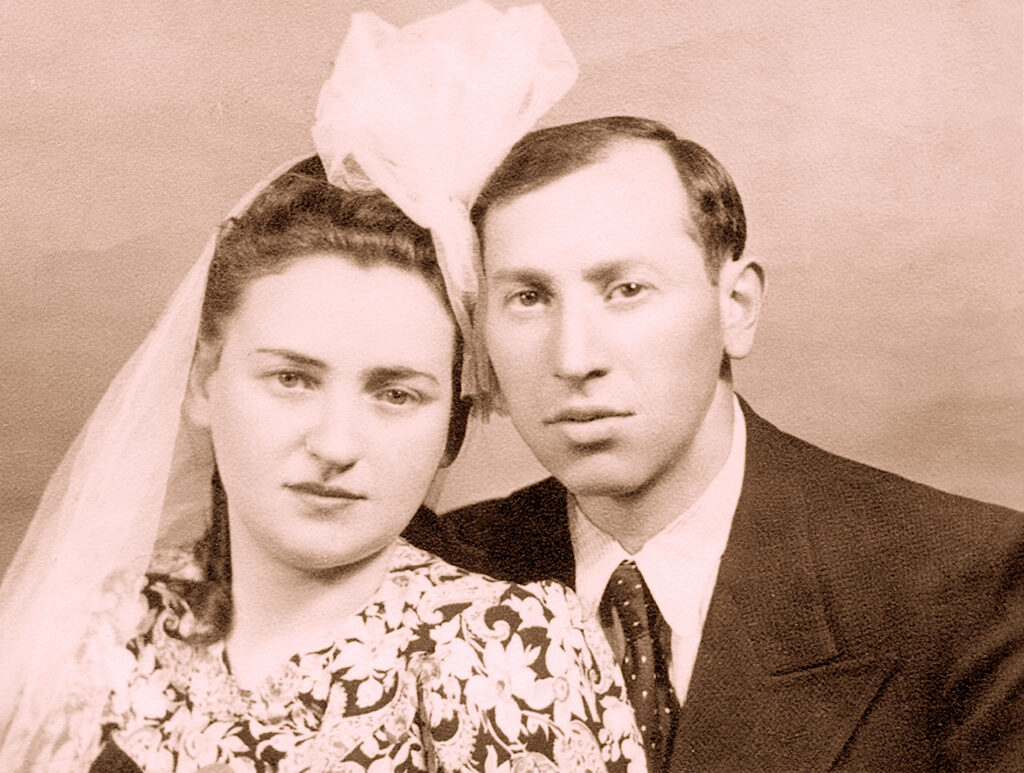

Simcha, my abba, who had fought in four armies — the Polish army before World War II, the Byelorussian Partisans during the German occupation, the Red Army and its liberating forces, and the Israeli army during the Sinai War in 1956, in Moshe Dayan’s troop, was killed by a young careless driver. A fighter, and not a victim. This time he was not given a chance to fight.

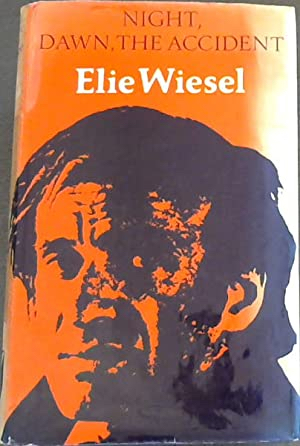

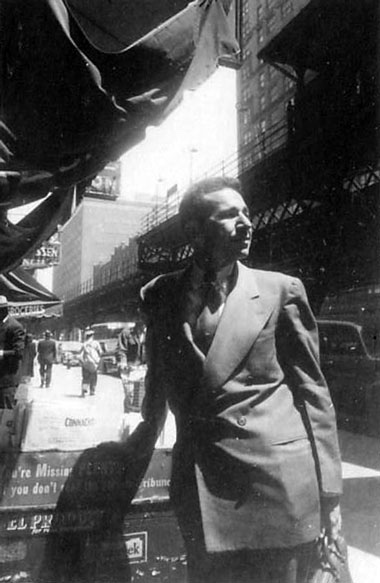

Wiesel did not know my father, but nonetheless, identified with being hit by a vehicle. Shortly after emigrating to the United States, in 1955, to become a permanent correspondent for an Israeli newspaper, Wiesel was hit by a taxi while crossing the street. He was recuperating in New York for almost a year, all alone. A fictionalized version of this incident is portrayed in his novel The Accident.

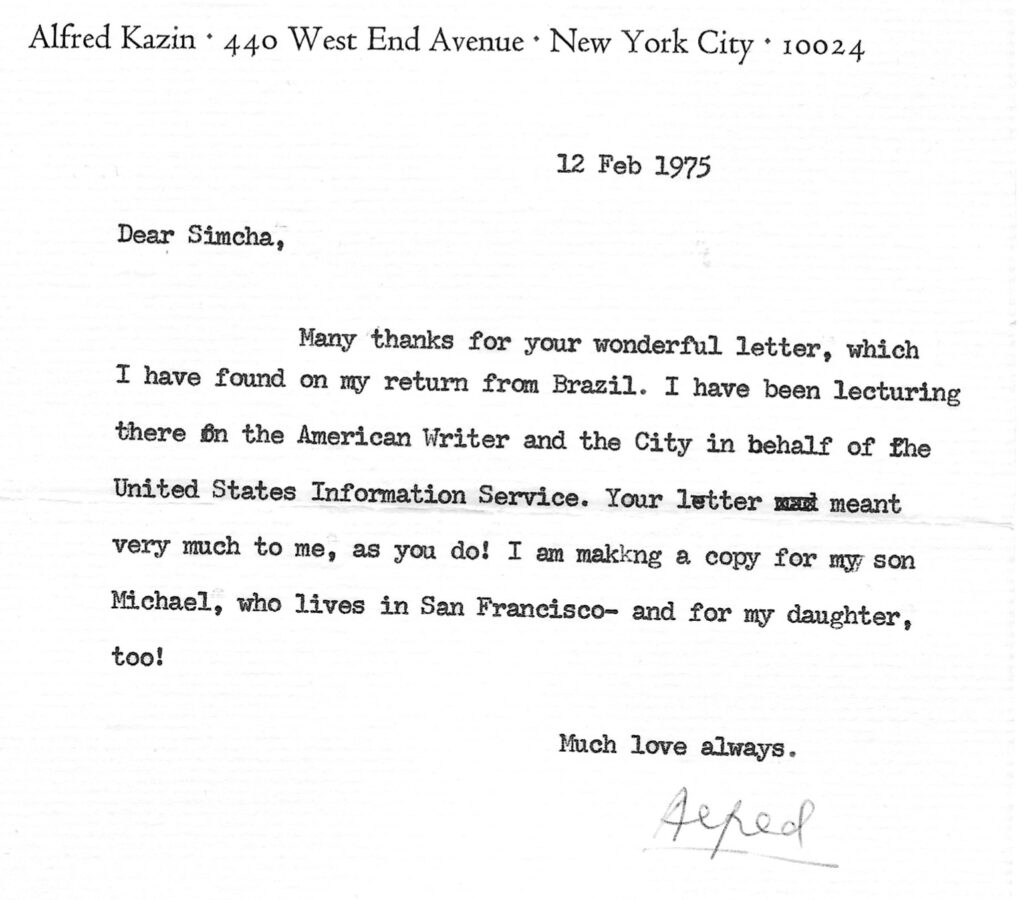

My father was a letter writer. In letters to his cousin Alfred Kazin, a central figure on the American literary scene during the last half of the twentieth century, he wrote about his life in Illya, Byelorus after the Germans occupied the area. In my possession is the “thank-you” letter that Kazin sent my father, February 12, 1976.

Kazin’s archive is housed in a room at the New York Public Library devoted to his work and correspondence. Missing in the Kazin archive is this important treasure. All that is left of that letter is two paragraphs quoted in Kazin’s New York Jew.

“At six in the morning the Nazis surrounded the town and captured approximately two thousand men, women, children. They took them outside the city. They undressed them naked. They lined them up against the walls of a warehouse. They shot them dead. The bodies fell into a huge burial hole. The many living yet with the dead. Indiscriminately the Nazis poured gasoline and set the bodies in flame. I was working as an apprentice in a baking shop. The Nazis walked into the shop and asked are there any Jews present. A Christian boy who worked with me said no, there aren’t any Jews. The boy directed me to the shabby cold attic where he locked me in from the outside. From the attic I heard the cries and shouts from the people in the city. Among the people killed in that crowd were my sister Sheyna and her husband.

“We were liberated 1945 by the Americans at eight in the evening, April 28th. Your soldiers were very nice but did not understand why we were in ‘prison.’”

Sheyna was my father’s aunt, not his sister. She was also Kazin’s aunt, his mother’s sister. My abba often spoke of Sheyna and Hillel Kapelovitz who were childless. They welcomed him to their home when he had to escape killings of Jewish men in Vilna after his troop, along with the rest of the Polish army, disbanded when the Germans defeated Poland at the start of World War II.

Kazin’s highly acclaimed intellectual memoir blatantly distorts his encounter with my father, mother, and me in a displaced person’s camp near Salzburg, Austria. My parents were in a Displaced Person’s camp in Kassel, Germany, and I was not even born yet when in reality Kazin visited Camp Riedenberg in the summer of 1947. He was participating in a six-week seminar in American studies known as the Salzburg Seminar with other American luminaries such as the anthropologist, Margaret Mead. One day he climbed over the fence and gave out “chocolate bars, bobby pins and razor blades” to a crowded “unkempt, dirty” room of refugees. Kazin recorded in his journal that a woman said: “Everybody has gone home now, …only we are left; we have no home to go to. You are American Jews,… you American Jews—do something!”

In contrast to the description in his journal, Kazin fabricates an entire scenario about my parents in New York Jew. Supposedly, my father “was a camp policeman” and my mother “was his brother’s widow” and I was my father’s “brother’s child.” And Kazin continues with this imaginary scene of my father showing him letters from relatives from Rochester, which we never had. Then my father tells his story and my mother, whom Kazin describes clutching me in her arms, and she follows with her separate war ordeals. Never mind that I was not born until a few years later. Kazin alludes to my mother telling him her story every time they spoke, and he felt she was back there when the Germans invaded her town in 1942. Historically, Wishkow, 50 kilometers outside of Warsaw was invaded on September 1, 1939. Kazin conflates past and present and distorts history.

The first edition of New York Jew was published in 1978. In retrospect I cannot understand how I did not challenge Kazin about his fabricating his encounter with my parents and me. He was teaching at the Graduate Center of City University of New York when I was a graduate student in social and personality psychology. On a few occasions we had a drink together on the 18th floor of the building, and we also took the subway together to my parents’ house for an occasional Friday night shabbat dinner. One day Kazin and I were in a crowded elevator together at the Graduate Center and he blurted out, “You are friends with Elie Wiesel.” I wasn’t invited for drinks again. We ran into each other at various literary events in New York City and exchanged casual greetings, and saw each other at a few family celebrations.

Not until almost ten years later, in 1989 when Kazin wrote an essay in David Rosenberg’s edited volume of Testimony, did I really understand why my association with Elie Wiesel would be greeted with such venom. After all, Kazin had written the seminal review of Night, when it was published in English in 1960. He called it a “piercing memoir.” Kazin was most laudatory when he wrote, “What makes his book unusual and gives it such a particular poignancy among the many personal accounts of Nazism is that it recounts the loss of his faith by an intensely religious young Jew who grew up in an Orthodox community of Transylvania. To the best of my knowledge, no one of this background has left behind him so moving a record of the direct loss of faith on the part of a young boy.”

After writing the review, Kazin asked to meet Wiesel and the two had an intimate relationship for a decade. The two would often meet on a park bench in Riverside Park on the upper west side of Manhattan, they talked for hours about the student revolts in France and Columbia University, Wiesel’s amazement at American Jewish writers’ openness about sexuality. Wiesel was often a dinner guest at the Kazin’s home, and the two were frequent speakers on panels together and would attend each other’s lectures.

For Kazin, Wiesel was his “Holocaust.” When Wiesel was becoming more of a public figure, and soon an icon in the Jewish community, and later in American society, and ultimately internationally, Kazin shunned him. He did not include Wiesel’s writing in subsequent literary anthologies.

When I arrived in the United States, in 1959, with my parents and younger sister, Gila, I had no idea who Alfred Kazin was in the world of letters. I only knew that his mother Gitta Fagelman Kazin was my father’s aunt. My grandfather Berel had brought Gitta to the United States in 1908, and they settled in New Haven. Berel had left his wife and daughter Sara in Dokshitz to make money to bring his family to America. When Berel sent a picture back home without a beard, his wife was forbidden by her father to immigrate to America. My great grandfather proclaimed, “You cannot be Jewish in America.” Berel returned to Dokshitz and procreated four other children.

Gitta was overjoyed with our arrival. She had one regret in that she was suffering from cancer and bemoaned the fact that she was not capable to help us to settle into our new home in the way she had envisioned. My father was sponsored by an owner of a bakery in Queens, and he went to work the second day after our arrival in New York. After working for a week, my father felt being taken advantage as a baker and he contacted another colleague and his wife from Europe who owned a bakery in the Bronx. The couple did not have children and my father was treated like a surrogate child. They wanted him to become a partner in the bakery and eventually take over the business.

Kazin’s mother would call my father daily and suggest that he get a job closer to home because travelling a few hours from Boro Park to Tremont Avenue in the Bronx is not a sustainable work situation.

Shortly after Gita died, Kazin invited my family for Sunday brunch. To me, he was my father’s cousin who took me around the corner to Broadway to Zabar’s to buy bagels, and lox and cream cheese, in a tiny store with one counter. His wife Ann Birstein, the novelist, stayed with my parents and sister. Their daughter Katie, almost 8 years old, was wearing a tutu when she returned from Riverside Park with her nanny in a white uniform. The apartment at 440 West End Avenue on the sixteenth floor had a glimpse of the Hudson River. The book lined apartment with high ceilings and wooden floors is still etched in my mind. A struck contrast from our train apartment that we shared with Gussie, the landlady of the building who never married. Since my parents worked long hours, Gussie was a built-in babysitter for us. Many years later the Kazin apartment was up for sale and I went to look at it for the sake of nostalgia.

Initially my father who spoke Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, German, Russian, Lithuanian had no common language with Kazin. His sister Pearl Kazin Bell, also a literary critic of notoriety, was more fluent in Yiddish than her brother, and could engage more readily in conversations. Kazin’s father Charlie was a frequent guest at our house for Shabbat dinners and Jewish holidays. Even though he was a socialist and an avid atheist, he enjoyed being with us, and even going to synagogue.

Like most Holocaust survivors, in the early years after liberation, they spoke among each other. Inadvertently, survivors created self-help groups before such a medium became a popular therapy. My father had a cousin, Genia Malecki, in whose family bakery my father apprenticed as a thirteen-year old in Vilna. The two would reminisce for hours on the telephone quite regularly.

Growing up I don’t remember asking my father too many questions about his past. One of the only books we brought with us when we immigrated to the United States was a Hebrew book, War of the Jewish Partisans in Eastern Europe, where my father’s name is cited.

I don’t think Kazin knew much about my father’s survival until Kazin asked him to write about his life under the German occupation. Coincidentally, this was around the same time that I was beginning my awareness groups for children of Holocaust survivors in Boston, and Elie Wiesel was beginning to teach the Holocaust at Boston University.

The Roots movement sparked a desire in many of us in America to delve into our own heritage.

Yuval Harari, a social philosopher whose ideas resonate with the pulse of our time, speaks to me as I am formulating the essence of what descendants of the Holocaust are now grappling with as their parents or grandparents have died or are terminally ill or aging gracefully. The psychological state of being is best described by Harari when he says that individuals get to know themselves better by knowing the stories in their mind and how they influence us.

Even though all Jews who lived under the occupation of the Third Reich or the Germans were persecuted for the sole reason that even one quarter of their ancestry was Jewish, the stories they told subsequent generations varied. Their story telling was not monolithic, therefore, the voices that children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors have in their mind vary. The narrative does not have to be detailed in order for a story to invoke fear and anger, or love for humanity.

Even though each Holocaust survivor’s narrative is replete with horrific images of hunger, humiliation, near death escapades, killing, stench, they are interspersed with some good stories — a stranger giving them a piece of bread, someone providing them information that saved their life, having a skill that made the difference between life and death, retuning back home and reuniting with a loved one.

It is not only the narrative of the story that guides its interpretation by the next generations, but also how it is told. These stories not only form values, but also contribute to the identity of the next generations.

What kind of values and identity do descendants develop when they were subjected to no stories or a fabricated story, only to be discovered during their elders waning years or after their death?

We are living in a zeitgeist of storytelling. Everyone has a story to tell.

Eva Fogelman, 2022.