Most of the world does not contemplate children as survivors of the Holocaust; surely it is understandable why this is the case. After all, the image that most have is that of Jews spilling out of the cattle cars, selected to go either “left or right,” and the children—all of the children—selected for death. An entire generation of European Jewish children was subject to the nightmare of Sophie’s Choice, except, of course, that the Sophie in the William Styron novel was a Polish Catholic, and so she was given a choice, though an impossible one. No Jewish mother was given the choice to save one of her children. The world expected that Jewish children would not be among the wretched, skeletal, survivors.

The child survivors were the true lost children of the Holocaust. While they managed to survive by dint of a confluence of miracles, instincts, and mazel (plain old luck), they were largely ignored in their life after Auschwitz. This, of course, was true of the adult survivors as well. The Jewish community in Palestine—the Yishuv—thence formed the new State of Israel, which celebrated an image, indeed an ethos, of the fighting, fully emancipated, and finally repatriated Jew. The new spirit of the Zionist age informed a societal agenda, to look forward and not back. Survivors were given the responsibility to rebuild their lives, and were told in effect not to speak of the past. And many of them did not wish to speak of the past, nor were they capable of revisiting the past.

Moreover, historians determined that, in learning about the Holocaust, nothing useful could be gained by talking to the survivors. An eyewitness to such an atrocity was deemed to be too damaged, too traumatized, and was therefore unreliable to offer an accurate account of what had happened. For historical purposes, the survivor was considered a biased witness, whereas the perpetrators were considered to be the ultimate truth tellers. Former Nazis were believed; Holocaust survivors were thought of as natural liars. Given this atmosphere of neglect and cynicism, the survivor had every reason to remain silent and be marginalized. This was even truer of the child survivors, who were considered too young to recall, or to understand, the significance of what they had seen. And, of course, there were so few child survivors that it was easy not to notice them.

It is estimated that only 6 to 7 percent of the Jewish children of Europe lived through the Holocaust and experienced liberation. It is impossible to calculate how many survived. Some are still hidden. What can be said with some measure of certainty is that the youngest were the most vulnerable; hence, most of the babies, toddlers, and preadolescents during that time did not live long enough to become adults. Their potential was destroyed before it could be realized.

Many children given to neighbors and convents in different states of the Nazi-occupied Europe for safekeeping were never returned. Yet, parenthetically and ironically, there were children who survived the Holocaust and died three years later on the battlefields of the new Jewish State, in the 1948 War of Independence. As soon as some of them got off the boats—after all they had been through—they were sent out with rifles to fight those who would kill them in their hoped-for homeland.

Although Jewish children had witnessed everything and lost so much before they matured, this cohort of Holocaust survivors—the children who survived—were largely ignored by their surrounding societies. Despite the huge focus on Anne Frank—the quintessential hidden child of the Holocaust—and her diary, the world did not seem to realize that there were children and teenagers who, improbably, survived genocide. These young survivors were neglected by virtually everyone and by every organizational entity that purported to care for those the Nazis had failed to kill. They remained anonymous in the culture, and fell under the radar of the Jewish community as well.

Scholars, social workers, and reparation authorities did not pay much attention to child survivors either. Orphaned child survivors were placed in institutions. For example, Kfar Batya, a kibbutz in the Mizrachi movement, took in Yaffa Eliach and Judith Kallman, who was also a “kindertransportee” in London. Roman Kent, now chairman of the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, and his brother were placed in an orphanage and eventually with families in Atlanta, Georgia. In some extraordinary cases, the children’s own survivor parents neglected child survivors. The parents had forgotten how to parent, or they did not see the point of parenting since the Holocaust proved that parents, no matter how fiercely loving and protective they wanted to be, could not protect their children from the Nazis and their collaborators.

The neglect that most of these children experienced when they were liberated resulted in complicated consequences to their identity formation and their ability to heal. Their survival was beyond human comprehension; it is not surprising, therefore, to learn that each child survived in his or her own unique way. After the war they soldiered on, refining their survival instincts in a new world where such extreme and otherworldly abilities no longer applied. The one skill they possessed—how to survive—was not easily adaptable. They were overqualified for the next step forward. No roads would lead them back to the past, and many did not wish to reclaim their past. There was no home to return to. An example of such a child is Samuel Pisar, the noted international attorney, who was on his way to becoming a “murderer” until his aunt took control of him and shipped him off to school in Australia, where he was cared for by his adoptive family and able to reshape his life.

The Holocaust child survivors did not constitute a monolithic group. Young people who were thirteen or under when the Third Reich was established include those who were born in Germany in the 1920s and those born during the war in ghettos; there were children in hiding, or with a disguised parent who fled from place to place. The majority of them were born in the late 1920s and 1930s; and in Hungary, many still were born in the early 1940s. Formal education—or the lack of it—played an important role in these children’s lives as well. Many were upset that their schooling was interrupted and that their life circumstances made it almost impossible to continue their education after liberation. Edith Cord, born in Vienna, realized very quickly, by age eight, that education would be her ticket out of poverty. Her family fled first to Italy and then to France, where she was hidden in a convent school, and she already understood that she would never be able to matriculate unless she applied herself. Edith resented having to move from place to place, and each time she attended school she could not finish her courses because she had to flee. After the war, Edith completed six years of university work in two years and earned her degree in Nice. When Edith emigrated to the United States, she earned her doctorate, and her first career was that of professor of modern languages.

There were also other child survivors who managed to receive their education, and they did very well. The late Andrew Grove founded Intel; Jack Tramiel founded Commodore and Atari, the first personal computers; and Fred Taucher invented Domain Name Servers (DNS). Indeed, without their contributions, our world would be a very different place. Elie Wiesel and Yaffa Eliach were the first to teach Holocaust studies in the City University of New York. Jerzy Kosinski wrote novels and transformed himself into a man both of letters and of mystery.

At times these child survivors chose professions that were preordained, inspired by their wartime experiences. Nathan Sobel was a founder of NACHOS, a child survivor organization in New York. As a ten-year-old living on his own, he navigated his way through the streets and slept in back alleys of a major Polish city. His “street smarts” and “hands-on” understanding of the way a city works served him well when he became city planner in New York. Roman Kent always says he earned his PhD in Auschwitz. Of course, they all knew that actual universities did not offer this kind of a curriculum. A real and more useful academic degree would eventually be practical. Many child survivors became miserable knowing that a formal education might ultimately be denied to them as they desperately reentered the world. Ernest Michel, another Auschwitz survivor, became one of the United Jewish Appeal’s most prominent executives. In Auschwitz he dreamt of organizing a World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors; in 1981 he did exactly that, yet he always felt he was educationally inferior to his peers because he did not finish sixth grade. That changed after he received two honorary doctorates—one from the City University of New York and another from Yeshiva University.

For child survivors who decided to struggle with new languages and who were determined to make their own way in their new lives, the possibilities were endless. Many of them came naturally to the helping and healing professions because they could empathize with pain and suffering. Others, especially those in Israel, took different paths. After receiving their educations on kibbutzim, they became career officers in the Israeli army, scientists who helped build Israel’s defense industry, doctors who built medical systems, and teachers—all for the purpose of protecting and saving the Jewish people.

Some became government leaders. The former Dutch minister of the interior, member of the senate, and mayor of Amsterdam, Ed van Thijn, was incarcerated in Westerbork; in Israel, the late Josef Lapid became the head of the Shinui Party in the Knesset and served as justice minister. The late Tom Lantos, a survivor and a member of the United States House of Representatives, played a major role in American foreign policy.

Just as professional identity could be influenced by experiencing persecution and losses, so could one’s Jewish identity. Despite the initial diversity of Jewish identification among the child survivors, for many becoming a Jew is a lifelong process that is changing to this very day. There are child survivors who are just discovering that they are Jews, while others intensified their Jewish religious observance after liberation. For example, the head of the Boston University Hillel, Rabbi Joseph Polak, survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp with his mother. Before the Holocaust, it was not so obvious that he would become a rabbi. His Jewish future was sealed by a bargain his mother made with God. While she was a prisoner, Rabbi Polak’s mother, much as Samuel the Prophet’s mother had done, swore that if she survived with her son she would raise him in the Orthodox tradition. She kept her vow, and now her son carries on her legacy by teaching his students how to be Jewish. In 2015 he published a memoir After the Holocaust the Bells still Ring, as a way of unearthing his past of an infant child survivor.

Some child survivors, used to hiding and concealing their true identities, were ambivalent about identifying themselves as Jews. This was certainly true of novelist and lawyer Louis Begley, a past president of the writer’s organization PEN American Center. His autobiographical novel, Wartime Lies, describes how he and his mother survived the Holocaust, although in the book, the adult is his aunt. For whatever reason, he refuses to participate in Holocaust commemorations and organizations and refuses to address the subject publicly. Child survivors such as Begley, who carry rage and ambivalence, need to “heal.”

In order to heal, individuals undergo the process of mourning, which ultimately results in the channeling of feelings into creativity. When a group is victimized, the healing of individuals is dependent on a convergence of personal characteristics, past socialization and experiences, and the social situation. The validation from others of pain and suffering enhances the potential for restoring the self. For child survivors of the Holocaust, this necessary step came very late; nonetheless, even at this late date, sixty-five years after the war, such recognition of suffering is making a difference in their waning years. Since most child survivors received little or no validation of their traumatic childhoods, their capacity to mourn and heal was hampered. Older survivors wrongly believed that those who were young during the German occupation did not remember what happened to them. But the children, even if they had not yet learned to speak, remember very well being forced out of their houses into ghettos, or escaping in the middle of the night to hide with neighbors or total strangers. They remember changing their names and their family narratives to take on new identities, or living with other children in orphanages, convents, or Christian boarding schools; and there are those who remember deportations. Older survivors assumed that these children did not see, smell, touch, hear, or feel what was going on around them. When adult survivors got together with other adult survivors, the child survivors sitting at the same table or eavesdropping on the conversation about the war were excluded. An adult survivor mother rarely asked her child, “Do you remember your father?” If Jewish children had non-Jewish rescuers, in many cases, their survivor parents prevented them from contacting the rescuer out of fear over the child’s competing loyalties. But the genie could not stay in the bottle forever. The children’s emotions would eventually come out.

In 1979, when the Holocaust survivor movement came alive and spread to every corner of the world, child survivors took advantage of the opportunity to bear witness. Instead of remaining in a state of psychic numbness and social withdrawal, they began to search for others with similar backgrounds with whom they could mourn and share, and their collective voice began to be heard. For the first time, empathetic listeners provided opportunities to help child survivors do the inner work of integration. This integration starts the process of incorporating the past into one’s identity and provides ways to mourn. But mourning is not so simple. While they do remember, it is challenging for child survivors to tell the story of what happened to them because they do not remember events as a sequential narrative. They remember fractured images, especially if the memories occurred in their preverbal stage. Child survivors remember incidents kinesthetically, as physical memories.

After years of being told they were too young to remember, child survivors admit there is, what the psychologists would call, some narcissistic gratification in telling their stories their own way, and this has happened more often in recent years. As the older survivors become incapacitated and curtail public appearances, child survivors are sought out and asked to share their stories with the world. This validation of their pain, suffering, loss, and adaptation makes child survivors feel understood, often for the first time. That others want to know what happened to them enables them to feel that they, too, along with the older survivors, can contribute to the recording of history.

In the mid-1970s, as a daughter of survivors involved in the Holocaust education and commemoration movement, I became involved in raising consciousness about the plight of child survivors almost by accident. I was leading groups for sons and daughters of Holocaust survivors in Boston, when I stumbled across child survivors for the first time. It happened when a potential group member approached me and said: “I saw an ad that says you’re leading an awareness group for children of Holocaust survivors. I don’t know if I belong.” I asked to meet with her to discuss it, and it turned out that she was not alone. There were a number of prospective group members who were children during the war and who had at least one parent who had survived. These former children described feeling like members of both the survivor community and the second generation—having struggled with their own unique psychological dynamics.

As a result, I organized what became known as intergenerational groups. The child survivors later called themselves the one-point-five generation, caught between the first and second generations. There were soon more avenues available to them for sharing their stories. The Center for Holocaust Studies in Brooklyn, founded by Dr. Yaffa Eliach and Stella Wieseltier in the late 1970s, was one of the first oral history projects in the United States that made a point to include child survivors. In 1981 psychoanalyst Judith Kestenberg initiated the International Study of Organized Persecution of Children, a project of Child Development Research, which to date has interviewed fifteen hundred child survivors. She, her husband Milton, and I organized monthly meetings with child survivors who had already been interviewed and child survivors who would be interviewed, and a few who never shared their testimony. As time passed, such groups and interviews were held in other major cities around the world, and child survivor organizations were established and flourished.

In the late 1970s, Myriam Abramowicz and Esther Hoffenberg directed and produced As If It Were Yesterday, a film about hidden children in Belgium. After showing her film worldwide and meeting many hidden children, Abramowicz had a vision, that of bringing child survivors together, such as Ernest Michel and the older Holocaust survivors had done at the World Gathering in Jerusalem in 1981. She approached Jean Bloch-Rosensaft and me to turn her vision into a reality. With the help of Judith and Milton Kestenberg of Child Development Research and the Anti-Defamation League, the First International Gathering of Hidden Children was held in 1991 on Memorial Day weekend in New York City, where sixteen hundred child survivors validated their own unique suffering and survival. Particularly affected were the hidden children. As the upcoming event was written about in Newsweek and New York magazine and in local newspapers, hundreds of child survivors started to come out of hiding. As had been the case with the World Gathering, this event also provided a major opportunity for communal mourning, something that is vital for survivors recuperating from historical trauma. The First International Gathering of Hidden Children gave the “children” an opportunity to mourn together in a collective voice. But first they had to accept that those they mourned were gone forever.

In each survivor’s recovery, there comes a moment of realization that loved ones are indeed dead. Every psychological process of mourning begins with shock and follows set stages that are dynamic, not static. At times they overlap, and can reverse or replay themselves during the course of a lifetime. For child survivors of the Holocaust, mourning is even more complex because of multiple deaths and the chaotic, life-altering circumstances surrounding the experience. Every child survivor has to mourn a multitude of relatives he or she knew and did not know, or knew and did not remember.

There are child survivors who witnessed the actual murder of a parent, a sibling, a grandparent, or other relative. That indelible image continues to be their living nightmare, etched in their minds forever. Some witnessed the slow death of the person they loved as they withered away from starvation or disease. For others the shock came after the war, from seeing a name on a list or being told that someone was dead. That permanent loss destroyed the fantasy that sustained the child, who had hoped that a loved one was still alive. That sense of hope went a long way toward providing a will to live under unbearable conditions. Now that hope was gone, and shock was left in its place.

After liberation, most survivors experienced an unconscious resistance to giving up the defense mechanisms that served them well under extreme conditions of terror. That attitude leads to the second stage, denial. Often, when one is jolted into accepting the death of a loved one, denial takes over and serves as a coping mechanism. But according to popular wisdom, “Denial is not a river in Egypt.” It is a painful state of being. That is why, in many cases, denial stretched into months and years before the person could enter the confrontation stage. When denial is a defense, there is resistance to giving up the hope that protected the victim from anxiety and from reliving a nightmare.

There were those who discovered only after the war that a loved one had died. But when a child witnessed the death of a parent or loved one under extreme conditions of terror, there was no opportunity to mourn at all; the situation provided no physical or psychological space in which to grieve. The enormity of the process of adapting to life after liberation sapped all of one’s energy. Many children were being handed off to strangers in places completely different from what they knew. Adults were making up for lost years, establishing new identities, moving from being a “victim” to being a “survivor,” and had no time to lavish care on the children. Most often that also meant physically moving from place to place until a permanent home could be found, and establishing new relationships, communities, and occupations far removed from their previous lives in Europe. Child survivors leaving Europe had to adjust to completely new cultures and languages, an adjustment that interfered with the stages of mourning. Under those circumstances, it often took an external trigger or a personal encounter with death to jolt an individual into delayed mourning many years after the deaths of his or her loved ones. The external triggers could be as simple as watching a movie and having flashbacks, or losing a spouse or other loved one, which released a flood of emotions that transcended the immediate loss and incorporated losses from the past that were never mourned.

Additionally, there are those who are forever trapped in denial, because moving from denial to confrontation requires established facts to prove that the person is indeed dead. In many cases, such information is impossible to find. And sometimes information comes in unexpected ways.

One of my own case studies is about Paulette, who was born in France in 1935 to parents who fled Germany shortly after Hitler came to power. For many years, although she hardly remembered him, she struggled to grieve for her father, who was deported to the Drancy internment camp near Paris when she was just seven. Her mother hardly spoke to Paulette about him. I encouraged Paulette to check the Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfelds’s book on French deportees, where she found the date of her father’s deportation to Auschwitz. But without an official date of death, it was difficult to engage in mourning. By the time she was ready to ask questions, Paulette’s mother had been diagnosed with dementia and could not offer any answers. Then, sixty years after liberation, Paulette received a telephone call from a woman in Paris, who had found her father’s suitcase in an attic in a town in the French Pyrénées where they had hidden; there were yet a few people still alive who remembered them.

With great trepidation Paulette made plans to retrieve the suitcase and meet the people whom she, too, had known in childhood. She learned what a kind, intelligent man her father was, and how well he was liked by the townspeople. When Paulette was handed the suitcase, she became very emotional. She could not believe she had her father’s papers. On one of the last pages of his diary, he wrote “Merde, merde, merde.”

“It must have been a terrible day,” she said.

What Paulette discovered was that her father had made every attempt possible to save his family by pleading for refuge from people around the world. He never received responses to his pleas. His devotion to his family was clear from his papers; but while she was growing up, her mother had given her a different impression, and Paulette assumed her father had abandoned them.

To cope with the uncertain facts of her father’s death, Paulette began the next stage: confronting his death. She worked on a scrapbook that combined photos, artifacts, and a narrative of her life to share with her own family. This became an all-consuming, painful venture that forced her to put her experiences into words. It was overwhelming. Although she continued to write, she handed the suitcase and its contents to the person assisting her, and asked him to review the information for her. She could no longer handle the emotional flooding the papers provoked.

A few weeks ago, Paulette called to say that her daughter-in-law had received a phone call from the Looted Art Registry, who found two rare books in France with bookplates indicating they had belonged to her grandfather. The person who provided the information also let her know that her father was on convoy 62, which arrived in Auschwitz on November 20, 1943, and that he was killed on November 30, 1943. Her first response was, “I never knew his yahrzeit.” She went on to say that she thought he had died in April or May 1944.

A different kind of “knowing” sets in when one has an actual date of death. Suddenly Paulette’s memory was sharpened. She now remembers the bombing of Paris, waking up in a bomb shelter, and going out with her father to empty her potty near a tree. She remembers different locales she fled to with her mother, with or without her father, and where she celebrated her birthdays. She remembers how, during the winter, her father fetched water from a frozen well by breaking the ice and how they grew vegetables in the spring. She has many more memories, but the important one for understanding the psychological impact of her years as a hidden child who confronts her father’s death and his love for her, are various unconnected vignettes or images: when she cut herself while helping a neighbor peel potatoes and was afraid to go home because she had been spanked twice by her father when she was rude to her mother. The first time she was spanked by him, she had asked her mother to teach her to crochet, and her mother had no time. The second time, she had tangled up some wool, and her mother said she had no time to fix it.

Paulette also remembers going to town with her father and holding his hand, but he was distracted, in deep thought. She remembers he chain-smoked and that he had a pink onyx ring. She also remembers the lullabies he sang to her. The last time Paulette saw her father, he brought her a pastry she shared with an older playmate who was hurt when he fell out of a tree. Her father encouraged her to share the pastry with the boy. After her father was deported, Paulette’s mother took her across the Swiss border. In a foster home there, Paulette learned to pray, and began to ask God to protect her father. Many months later, her mother told her that her father had been killed. When Paulette realized that God had not answered her prayers, she stopped believing in anything. She also did not respond appropriately, because she had not seen her father for a very long time. For years, Paulette had a “thing in her head” and believed he could not be dead. “For years I used to think, who knows? Intellectually I knew my father was dead. Yet when I saw the movie Tomorrow Is Forever I thought he might be alive.”

Her mother did not tell Paulette that her father had tried to help them escape. Paulette told me, “I always thought that if he would have loved me enough, he would have escaped from the camp. I didn’t know that if he escaped others would get punished. He had a strong sense of right and wrong and wouldn’t want to jeopardize other lives. He worked in the underground and he went to Paris because his mother was dying and he got caught.” Paulette was probably also angry that he spanked her and sided with her mother. This anger is less conscious than the anger she felt for being abandoned. Paulette now understands that she is mourning her father while also mourning the fact that he did not love her unconditionally.

This summer Paulette plans to go to Europe, and she hopes to retrieve the books that have brought her to this point. She wants to continue working on her creative project and may even write a book when it is finished. Paulette’s story exemplifies the complexity of accepting the fact that a loved one has been killed, and she now faces the fourth stage of mourning: the expression of feeling. How can she be angry with someone who suffered so much and was killed in Auschwitz? The feelings that emerge in this phase are survivor guilt, anger, rage, depression, a sense of helplessness, and a need to undo the suffering of the deceased. At times survivors get stuck in this stage and feel too guilty to enjoy their own lives because they feel they should have died instead. There is often an overidentification with the suffering of the deceased, and this can cause psychological challenges if one is stuck in this stage.

Politics can also be a trigger. Amazingly, glasnost in the former Soviet Union opened the floodgates of mourning for many survivors and child survivors. Child survivors wanted to search for their rescuers, and rescuers were searching for the children they saved and had given back to their parents, to relatives, or to Jewish agencies.

When I was director of the Jewish Foundation for Christian Rescuers (then housed at the Anti-Defamation League), a man called and told me his wife had been rescued in Lithuania and wanted to know if we could offer the rescuer financial aid. Our representative in Lithuania told us that that the rescuer, whom I’ll refer to as Drinka, wanted to visit the United States. The rescuer also sent a letter to the child she saved, Geula, who was then a fifty-one-year-old social worker, married with two children and residing in Pennsylvania. After liberation, Geula was retrieved and raised by an aunt because her parents did not survive.

After living with her parents in the Vilna ghetto for a year, Geula was hidden by a Lithuanian Christian family, whom her father had befriended while they were strolling with a baby carriage outside the ghetto. Geula had no memory of her parents of origin. Despite the fact that Geula was not eager to correspond with her rescuer, Drinka would write to her regularly. Eventually, Drinka lost touch as Geula’s family moved around. Once contact was renewed, Geula was ambivalent about seeing her former rescuer, but was being pressured to do so by the local rabbi. He told Guela that the least she could do to repay her rescuer was to bring her to the United States. Geula felt terribly guilty and asked me what she should do. I replied, “Well, if you don’t want to bring her, you don’t have to.” She was relieved when a professional told her she could stop feeling guilty.

At that point, I asked Geula to tell me her story. The story she told came from her aunt; Guela was too young to remember events in a coherent sequence. Geula’s father worked outside the Vilna ghetto and returned every night. One day he saw a Christian woman with a stroller and asked her if she would hide his little girl. When Drinka shared this request with her husband, he said, “It must be a sign from God that you were walking there at just that moment. We must take the child.” The following night they went to the appointed place and picked up a sack containing Geula, then just a toddler. Her biological father also gave them a piece of paper that had Geula’s name written on it. The couple had two children of their own and realized that their neighbors would be suspicious if they had a third child without a pregnancy, so they moved to a neighborhood where no one knew them. As we talked, Geula suddenly remembered that when she was about four years old, she was crying from a nightmare. She went into Drinka’s bed and wanted to be held. Instead, Drinka put a finger over her mouth to stop her from making noise and sent her back to her bed. This frightened Geula, and she was very scared of Drinka after that incident. Verbalizing her fears made Geula aware that her childhood feelings about Drinka were not appropriate in the current situation. Geula changed her mind about the visit, and made plans to bring Drinka to the United States and to have her honored by Yad Vashem as one of the Righteous Among the Nations of the World.

Confronting the past, expressing the emotions that come with it, and then doing something meaningful, such as recognizing goodness and paying tribute to a former rescuer, is the essence of channeling feeling into the final stage of mourning. What is of interest is that now, more than sixty-five years after the war, some child survivors are just now shedding the state of denial and are moving into confrontation.

The Hidden Child Foundation in New York receives numerous telephone calls that ask for help in the search for lost family members. But what do you do if you have no information to go on? How could one move from denial to confrontation under such circumstances? Wladyslaw Sidorowicz, a doctor from Ukraine, thought he was Catholic until recently, when he discovered that he and his father did not have matching DNA. His parents were Ukrainians who married before World War II. They had a daughter as well. In retrospect, he recalls that he felt he did not belong to his family. He was different. He had ash blond hair and green eyes, while the rest of his family had black hair and brown eyes. He was academically oriented in a family where intellectual pursuits were forbidden and punished, and although his sister was eight years older than he was, he helped her with her homework.

Wladyslaw’s father spent some time in the Gulag and then joined the Polish army formed by the Russians. After the war, the family was reunited in southwestern Poland, but his father had become a different man, a raging alcoholic who was physically abusive. His mother protected the boy from his father’s rage, and she paid a heavy price. Later, Wladyslaw finished medical school—third in his class of 250—and when his father fell ill and was hospitalized, Wladyslaw read the medical chart and saw that their blood types did not match. That incident triggered a decades-long quest to find his real father, because his mother refused to give him any information about his past. In 2007, his own daughter suggested that he get his DNA tested, and he was shocked to learn that his DNA is Semitic and that he was not biologically related to the woman he always knew as his mother. She had previously alluded to this, albeit vaguely, by saying to him, “The Sisters saved your life.” He estimates that in 1945, when he was between seven and sixteen months old, he was cared for by nuns, who gave family in Ukraine.

“Can you imagine not knowing who you are, what your real name is, or when you were born? Who was left in your family?” he asked. The good doctor moved to South of Fallsburg in upstate New York, where he now lives and is continuously searching for his lost identity as he studies Judaism. In this case and in others like it, the movement from denial to confrontation is almost an impossible task. We are all defined by our roles in our family, our sexual identity, religious identity, professional identity, and national identity. Living without closure and without an identity impedes adaptation to the real world, and as a result, to this day some child survivors are affected.

At the end of the war, the Jewish children who were hidden were not brought to the town square to be given back to their families or Jewish agencies. Jewish organizations had to hunt them down; lawsuits were rampant in Poland and Holland as families fought to keep children who were not their own. In addition to mourning their own biological parents, many child survivors also had to mourn their foster parents. This became very complicated for those who had a surviving biological parent, or both parents, who wanted loyalty and love expressed to them and not to a stranger. They had no understanding that as a result of their pressure, their child had experienced a loss.

The final stage in the mourning process—the search for meaning—is often misunderstood. Survivors are not searching to find meaning in the murder of their loved ones, or meaning in why God did not protect them from starvation and degradation. They leave that to the philosophers and theologians. Each survivor searches for a way to lead a meaningful, productive, enriching life in the here and now. Some want to assuage their feeling of survivor’s guilt by showing others that they are worthy of having survived, so they search for ways to do meaningful work, or choose to become involved in a mission that will make the world a better place. Child survivors grapple with transcending a civilization that went awry. This is a creative process, a form of searching for meaning that is not always conscious. There is a driving force that a survivor may feel but cannot necessarily put it into words. Literary critic Lawrence Langer is correct when he claims he is “dubious” about “wresting meaning” from the literary texts of annihilation. The creative works of survivors or their other endeavors—whether they are work-related or avocational—force the survivor to work through the emotional flood that engulfs them. That effort is of utmost importance because the goal of this phase of mourning is to channel those overwhelming emotions into other avenues so that the survivor can function properly on a daily basis.

The late George Pollock, a psychoanalyst, taught us that creativity is derived from mourning. In psychoanalytic parlance, it is a form of sublimation, and hence a defense against overwhelming feelings. Yet, the creative process does not always alleviate intense emotions and is not a panacea.

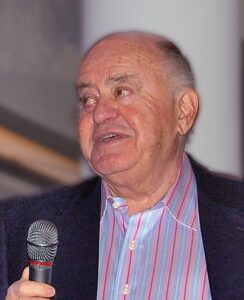

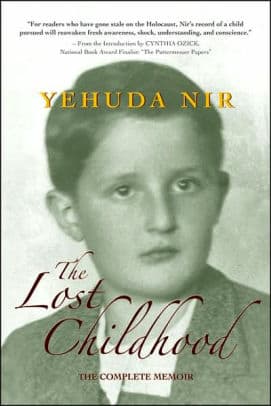

Dr. Yehuda Nir, a psychiatrist, wrote the wartime memoir Lost Childhood.

In it he recounts how his mother survived by working as a maid for a Nazi and how his father was killed. As a boy in hiding, he had many close calls and continues to be consumed with rage toward the Germans. He uses any public forum he can find to express that rage, first in his book and now in the production of an opera based on his book. Nir’s rage borders on irrationality when he says that all the rescuers honored by Yad Vashem are bogus, and insists there were no good Germans, Poles, or Hungarians. Nir’s case proves that trying to channel deeply rooted emotions through a creative outlet cannot always be successful.

Writing—the literary response—has become a significant way for child survivors to channel their emotions and engage in a creative search for meaning. There are many writers in this category, and the Israeli author, Aharon Appelfeld, who survived the Holocaust as a child in Bukovina, is an excellent example. Thane Rosenbaum, novelist, essayist, literary critic, and law professor, has said that Appelfeld’s novels follow a literary motif common to many books written by children who survived the Holocaust. The child is often depicted as born into a world of hiding—a perpetual game of hide-and-seek where the idea is to never be found. Often they are represented as hiding as a Christian, whether in a convent or a farmhouse or racing through forests and towns with an older relative or non-Jewish rescuer. But the reader understands that these children are essentially alone. Surely this is how people understand the circumstances of the child in Jerzy Kozinski’s The Painted Bird. In Appelfeld’s new autobiographical novel, Blooms of Darkness, a Jewish boy is saved by a prostitute, who keeps him in her room and hides him in her closet as she services her clients, many of whom are German officers. In the morning, she retrieves him and cares for him; and as the war comes to an end they must flee, and it is the boy who rescues the prostitute who had rescued him.

Unlike Applefeld, most child survivors are not writers by profession and often just have one book in them. When they write, it is a way to remember those who were murdered in the Holocaust. Their books provide an opportunity to speak in public, to get validation from readers and audiences, and to remember the dead collectively. This was surely true in the case of playwright Arte Shaw, a child survivor from Tashkent, who wrote the Broadway play The Gathering, in which a Holocaust survivor, who became an artist, takes his thirteen-year-old grandson on a bar mitzvah trip to Bitburg, Germany, to protest President Ronald Reagan’s plan to lay a wreath on the graves of the Waffen SS.

The creative approach can take many forms—the visual arts, film, theater, writing, performance, even architecture. It can be done by raising consciousness about man’s inhumanity to man through education and human rights work, or by working as lawyers or activists to help others in distress. Another way to search for meaning is by living a life that expresses the continuity of the Jewish people, and connecting to and recapturing the culture that had been damaged or destroyed. There are child survivors at the forefront of keeping the Yiddish and Ladino languages alive, who are immersed in studying Jewish texts, who are raising future generations who will grapple with the quality of Jewish life in the modern world. Some of them are even leaders of Hasidic sects in Brooklyn—for example, the Munkaczer and Dinever dynasties are headed by brothers who are both child survivors.

In every victimized group, myths are created to describe the members of that group. Anecdotal evidence instead of research is often used to support and justify those myths. But myths and legends can be laid to rest. Historical and psychological data now provide evidence of the coping and adaptation mechanism of the population of Holocaust child survivors. We now understand more clearly the enormity of the experience and history of child survivors. We face a twofold challenge: to avoid stigmatizing child survivors and at the same time to validate child survivors’ experiences, in order to enable each person to lead a productive life that has a positive impact on society.

The child survivors have taught us all that it is not possible to rush the mourning process, that grieving cannot be measured with an egg timer or a stopwatch. It is not a race. In the aftermaths of more recent genocides—Bosnia, Rwanda, Cambodia, Congo, Sri Lanka—survivors are often forced to speak too soon, when the wounds are too fresh. Many of those genocide survivors, many of them children, are simply not psychologically ready to speak. Truth and Reconciliation commissions, especially in South Africa, force the belief that in order to heal, survivors must immediately testify to what happened, to recount in their own words what they witnessed and how they feel about having survived with the knowledge that others died. We now know that while the intentions were sincere, the process of forcing victims to speak to their losses too soon is unreasonable and psychologically harmful.

What is most important is that genocide survivors be permitted to reenter the world of the living, to experience the simple pleasures of a warm bed or a gentle, reassuring hug, and a secure environment. There will always be time to speak and remember, but testimony, as moral and as important as it may be, is not a substitute for security. Survivors, and especially child survivors, who were forced to become experts in hiding, need to know that it is safe to come out. They are not easily convinced.

The silence will be broken, but not immediately. There is a fine balance between wanting survivors to speak too soon, or too late. It is the responsibility of those in the field of healing others to be patient for the sake of the survivors, and allow them to speak when they are ready. Healing is often a solitary process. Healers are enablers, but not magicians. Healers cannot make pain go away or disappear. They can only create environments where trust is restored and where healing can begin.

The author would like to thank Jeanette Friedman, Thane Rosenbaum, and Jerome Chanes for their assistance in preparing this chapter.